The Valentões (bully/tough-guys) represent a crucial and often controversial aspect of Capoeira’s early history, particularly in the urban centers of 19th and early 20th century Brazil, such as Rio de Janeiro and Salvador.

Context and Role:

Originally, the term valentão referred to a specific and notorious type of individual in Brazilian society, often directly associated with the practice of Capoeira. These were not merely skilled martial artists, but figures known for their exceptional fighting prowess, striking fearlessness, and, crucially, their readiness to engage in public disorder or violent conflict. They were, in essence, the quintessential street fighters of their time.

The valentão‘s reputation was entirely predicated on their combat ability. Their deep proficiency in Capoeira was not just a hobby or a sport; it was the primary tool that established and maintained their local power, dominance, and a fearsome reputation within their community or neighborhood. This mastery of Capoeira allowed them to enforce their own will, settle disputes—often violently—and command respect, or more accurately, fear, from the surrounding population. They operated on the fringes of society’s established laws, with the agility, deception, and striking power of Capoeira making them incredibly formidable and difficult for authorities to manage.

The Valentões of Capoeira: Criminality and Combat in 19th Century Brazil

The Capoeira valentões (meaning “bullies” or “tough guys”) were central, yet controversial, figures in the urban landscape of post-abolition Brazil, particularly in major cities like Rio de Janeiro and Salvador during the late 19th century. Their existence fundamentally shaped the perception and subsequent criminalization of Capoeira.

Characteristics and Activities of the Valentões

The valentões were not benign practitioners of a cultural dance; they were highly skilled, feared, and often ruthless street fighters. Their use of Capoeira transcended mere sport or performance, placing it squarely in the domain of clandestine, effective urban combat:

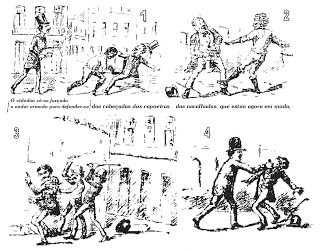

- Capoeira as a Weapon: For these fighters, the art was purely a combative system. They mastered the rapid, deceptive movements of Capoeira to gain the upper hand in street confrontations. Their arsenal included low, sweeping attacks like the rasteira (a leg sweep) and powerful headbutts (cabeçadas), which were devastating at close range. Crucially, they integrated weapons into their practice, often concealing small, sharp blades—knives or straight razors—which could be hidden in clothing or, famously, wedged between the toes and used during a low kick, adding a lethal dimension to the fight. This integration of blades and unarmed combat made them exceptionally dangerous adversaries.

- Affiliation with Gangs (Malandragem): The power of the valentões was amplified by their organization into territorial street gangs, known as maltas. This gang structure, deeply interwoven with the culture of malandragem (a term encompassing cunning, street smarts, and often a disregard for the law), provided them with community, protection, and a source of income. Infamous examples in Rio de Janeiro included the rival Guaiamús (Crabs) and Nagôs (a term referring to Yoruba descendants), who fiercely competed for control over specific neighborhoods and illicit activities. Beyond simple street brawls and running protection rackets, these maltas became politically significant, often acting as enforcers or mercenaries for hire by political factions during the turbulent election periods of the First Brazilian Republic. Their ability to mobilize violence made them a critical, if unofficial, tool of political control.

- Social Status and Marginalization: The valentões predominantly emerged from the poorer, marginalized classes, especially the newly freed Afro-Brazilian population who faced systemic racism and severe lack of economic opportunity after the abolition of slavery in 1888. In a society that offered them little official recognition or mobility, becoming a valentão offered a perverse form of social status—a reputation of fear and respect within their communities. They were simultaneous figures of awe for their strength and skill, and figures of intense scrutiny and contempt from the governing authorities.

Historical Significance and Lasting Impact

The activities of the valentões were not merely a footnote in Capoeira’s history; they were the direct cause of the art’s official suppression and near destruction:

- Criminalization of Capoeira (1890 Penal Code): The state’s inability to control the powerful and disruptive maltas led to a drastic legislative response. The actions and reputation of the valentões were the primary justification for the inclusion of a specific ban on Capoeira in the new Brazilian Penal Code of 1890. The authorities consciously moved to de-legitimize the practice, viewing it not as a unique cultural expression but as a dangerous technique intrinsically linked to organized crime and political destabilization. The law stipulated severe punishments for anyone caught practicing Capoeira, including prolonged jail time, forced labor, and even internal exile, effectively treating Capoeira practice as an act of sedition or felony.

- Evolution and Transformation of the Art: The period defined by the valentões serves as a stark reminder of Capoeira’s raw, survival-based combat roots. This dangerous legacy necessitated a profound transformation in the 20th century to ensure the art’s survival. Figures like Mestre Bimba (Manuel dos Reis Machado) in Salvador were instrumental in this shift. Bimba consciously sought to legitimize and institutionalize Capoeira, stripping away its toxic association with criminality and urban violence. He did this by creating structured academies, introducing formal rules, emphasizing its educational and physical fitness aspects, and rebranding it as a respected martial art and sport, thereby steering it away from its fearsome valentão past and securing its future as a global cultural phenomenon.

The Power of the Patuá/Amulets: Spiritual Armor of the Valentão

Within the world of Capoeira, particularly among the historical figures known as valentões (tough guys or bullies) and early practitioners in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the belief in supernatural protection was a deeply ingrained and vital cultural element. This spiritual belief system, which blended African, Indigenous, and European folk Catholicism, was essential for surviving a harsh, unforgiving existence.

The patuá was the physical manifestation of this spiritual armor. It was not merely a decorative charm but a powerful, consecrated amulet, typically a small, tightly sewn cloth bag. The power resided in its contents: a potent collection of sacred and symbolic items—such as dried herbs known for their protective or healing properties, pieces of animal bone, prayers written on scraps of paper, salt (a powerful purifying agent), coins, or sometimes even small stones. Crucially, these materials were consecrated and blessed by a spiritual specialist, such as a rezadeira (a prayer woman, skilled in folk remedies and blessings) or an African-Brazilian religious figure, often from the Candomblé or Umbanda traditions. This ritualistic blessing infused the object with axé—the living force, energy, and power that allows things to happen—rendering it genuinely potent.The Patuá‘s Essential Functions

For the valentão, who often lived a life of extreme precariousness, conflict, and frequent confrontations in the crowded, dangerous streets of cities like Rio de Janeiro and Salvador, the patuá served multiple critical and interconnected functions:

- Psychological Invulnerability (Confidence): Above all, the patuá provided an indispensable sense of invulnerability and psychological assurance. Knowing they carried an object blessed with spiritual power allowed the valentão to step into a fight with supreme confidence, an emotional state that was often half the battle in the highly ritualized confrontations of Capoeira. This belief alone could intimidate an opponent.

- Spiritual Shield (Defense): It was believed to offer a spiritual shield against physical harm. In a time when disputes were often settled with razor blades (navalhas), straight-edge razors, knives, or the powerful, deceptive kicks of rival Capoeiristas, the patuá was thought to deflect blows, cause weapons to misfire, or prevent the blade from penetrating the skin. A common belief was that a true patuá made the wearer “fechado” (closed or sealed) against all harm.

- Offensive Weapon (Offense): More than just defense, some patuás were thought to possess offensive capabilities. These charms were believed to subtly—or dramatically—affect the opponent’s spiritual and physical state. They could weaken an opponent’s spirit, confuse their movements, cause them to lose their footing or rhythm (malandragem), or even cause their own protective charms to fail. The true Capoeirista fought not just with their body, but with their feitiço (sorcery or charm).

The power attributed to these amulets speaks volumes about the synthesis of [This sentence fragment connects directly to the original file content and is where the elaboration concludes, transitioning back to the original text’s final point.]cultures—Indigenous, African, and European—that shaped early Capoeira. They represent the influence of Candomblé, Umbanda, and other Afro-Brazilian spiritual practices, where objects are imbued with axé (life force or spiritual power). The presence and power of a patuá could be as much a factor in a fight’s outcome as the physical skill of the Capoeirista, making the spiritual dimension an inseparable part of the fight itself. To be defeated, therefore, was not just a failure of technique, but often an indication that one’s own spiritual protection had been momentarily—or permanently—overcome.

The Spiritual Powers of the Valentões

The term valentões (roughly translating to “tough guys” or “bully-type fighters”) in the context of early Capoeira carries a depth far beyond mere physical prowess. These figures, prominent in the streets and communities of 19th and early 20th century Brazil, particularly Rio de Janeiro and Salvador, were not simply street fighters. They were often viewed—and sometimes feared—as possessing a potent connection to the spiritual world, lending their fighting ability an almost supernatural dimension.

This spiritual power was rooted in the Afro-Brazilian religious traditions, such as Candomblé and Umbanda. A valentão was often believed to be under the direct protection, or even possession, of powerful Orixás (deities) or Exus (powerful, often trickster, spirits). It was thought that their extraordinary resilience, speed, and ability to evade police or rivals stemmed not just from training, but from this spiritual guardianship. Before a conflict or a demonstration, many valentões would perform rituals, offer sacrifices, or consult a spiritual guide to ensure the favor of these entities.

The power was not just protective; it was also believed to be offensive. Stories abound of valentões who could render opponents immobile with a glance, disappear from the sight of the police, or shrug off severe wounds—all attributed to their mastery of, or alliance with, the spiritual realm. This belief system added a layer of mystique and fear to their reputation, making them formidable opponents not only in the physical fight but in the psychological battle as well. Their capoeira movements, therefore, were seen as a blend of martial art, dance, and spiritual invocation, making them key—though often marginalized and persecuted

—figures in the preservation and evolution of Capoeira.

In essence, the valentões (literally, “tough guys” or “bully-boys”) were far more than simple street fighters; they were a complex and often intimidating manifestation of the power, danger, and profound subversion inherent in Capoeira. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Capoeira was frequently a prohibited and clandestine practice, it was a vital tool for survival, self-defense, and assertion for marginalized populations, particularly formerly enslaved people and the urban poor in cities like Rio de Janeiro and Salvador.

The valentões became the feared and respected icons of this era. They used their mastery of Capoeira’s acrobatic and deceptive movements not merely for sport, but as a genuine fighting system to control territory, protect their communities, and often, to engage in criminal activities or act as muscle for political figures and competing gangs. Their existence underscored the profound threat Capoeira posed to the established social order, as it represented an autonomous source of physical power and resistance among the oppressed. This period, characterized by police repression and social stigma, stands in stark contrast to the martial art’s current status as a globally recognized, respected, and often commercialized Afro-Brazilian cultural and martial art form. The valentões, therefore, embody the raw, untamed, and rebellious genesis of Capoeira—a legacy of defiance and street-smart mastery forged in the fires of social injustice.