Hello Everyone,

This is the 1st of a 2 part article about WHAT I BELIEVE is the birth and spread of Capoeira from west Africa to Brazil, and the rest of the world.

The opinions expressed in this article are mine, and mine alone, based on research I’ve done on this subject.In this article, I will delve into the historical and cultural aspects that I believe contributed to the birth and spread of Capoeira from West Africa to Brazil and its subsequent influence across the globe. Through extensive research and analysis, I have formulated my own perspectives on this fascinating topic, and I am eager to share my insights with the readers. It is important to note that the views presented in this piece are entirely my own and are not reflective of any institutional stance.

As I unfold the narrative of Capoeira’s origins and evolution, I aim to offer a thought-provoking exploration that invites readers to consider the complex interplay of factors that have shaped this martial art and cultural phenomenon. Stay tuned for the next part of this series, where I will continue to expound upon this captivating subject, drawing from my in-depth exploration and personal interpretations.

First of all, I would like you all to watch this video.

Although the great Continent of Africa has it’s problems just like everywhere else, the fact is that many great ancient civilizations came from Africa, which in their day, and even to this day, were just as splendid and glorious as any other great civilization on the face of the earth. And, the people of Africa and the African diaspora have made many contributions to the western world. The rich history of Africa includes the ancient civilization of Egypt, known for its remarkable architecture, mathematics, and advanced understanding of astronomy. The kingdoms of Kush and Axum in East Africa were formidable powers, engaging in trade and diplomacy with ancient Rome and Byzantium. In West Africa, the powerful empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai thrived, known for their wealth, governance, and cultural achievements. These civilizations played a significant role in shaping the development of human civilization and the exchange of knowledge across continents. The African diaspora has also made indelible contributions to the Western world, particularly in music, literature, art, and the fight for civil rights. From the blues and jazz to the vibrant expressions of today’s artists, the influence of the African diaspora is deeply woven into the fabric of Western culture. It’s important to recognize and celebrate the rich heritage, accomplishments, and ongoing contributions of Africa and its people, both on the continent and across the globe.

And, in the country of Brazil, one of those african contributions came to be known as… CAPOEIRA.

There is a HUGE debate about the origins of capoeira.

…But I’ll share my thoughts about that, and why I think there’s a huge debate on another PAGE.

Right now, I just want to share MY thoughts on Capoeira’s history.

The comparison between the history and development of Capoeira and the martial art of Kajukenbo is indeed a fascinating exploration of the cultural influences and origins of these two unique practices. While Kajukenbo emerged as an American (Hawaiian) hybrid martial art in response to the specific context of violence in the United States, particularly in the Palama settlement of Oahu, Hawaii in 1947, its techniques, fighting strategy, and even the uniforms draw deeply from Oriental roots.

Similarly, the Brazilian art of Capoeira, which was developed in response to the dynamics of violence in Brazil, reflects a rich tapestry of African roots in almost every aspect of its practice. From the foundational techniques to the intricate fighting strategies, the vibrant music, the rhythmic way in which songs are sung, and the traditional instruments used, Capoeira is deeply intertwined with its African heritage.

The parallel between these two martial arts underscores how cultural influences and historical contexts have shaped their unique identities. Through their distinct but interconnected journeys, both Capoeira and Kajukenbo epitomize the rich tapestry of cultural fusion and evolution that defines martial arts around the world. This convergence of diverse influences serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of cultural heritage in shaping martial arts and their profound impact on societies.

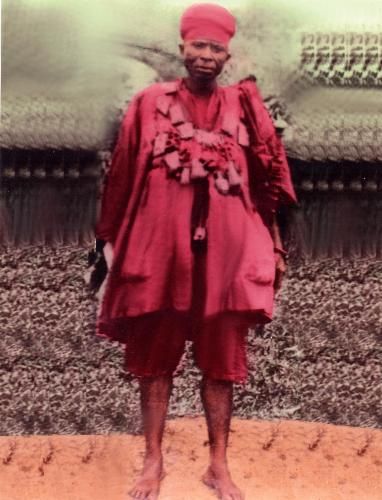

Think about it. Let’s say that you’re an african warrior, and in battle, you had your fellow warriors with you, along with your traditional weapons…

and your enemies had much the same weapons as you, and looked like you…

But after say, a battle with an enemy tribe, you were captured and sold to the portuguese, and get sent to brazil, to a whole new environment.

Your enemies now looked totally different…

And they had TOTALLY different weapons…

And you’re for the most part alone, or with a small group of fellow warriors, and all you have to fight with is basically, anything you can get your hands on…

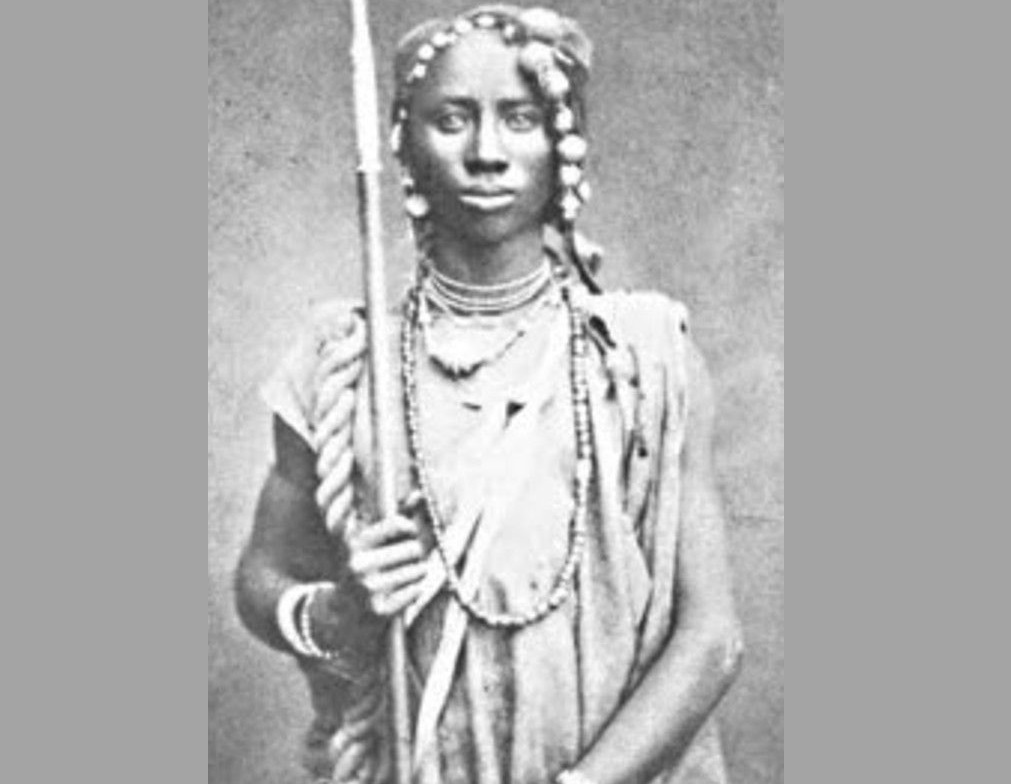

The evolution of your fighting style will be a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the human spirit. Rooted in the rich traditions of African martial arts, the techniques and philosophies passed down through generations will form the foundation of your approach. However, the inevitable encounters with diverse martial arts practiced by fellow enslaved African warriors, as well as the influence of your new environment, will impart a unique and dynamic quality to your fighting style.

The amalgamation of these varied influences will culminate in a distinctive form that is tailored to meet the challenges imposed upon you. This amalgamation, born from necessity, will equip you with the ability to effectively confront and overcome the adversaries that you are compelled to face. Embracing this evolution, you will not only survive but also symbolize the enduring spirit and resilience of your heritage.

Now of course there are some Native Brazilian and European influences as well, like the fact that the songs are sung in Portuguese (Even though there are MANY AFRICAN LYRICS as well), there is many references to Catholic saints (I’ll blog more about that on another PAGE), and they depict and celebrate the lives of the Brazilian people in general, and the Afro-Brazilian people in particular. The amalgamation of these diverse cultural elements enriches the fabric of Brazilian music, creating a unique and vibrant tapestry of traditions and influences. The Portuguese lyrics infuse the songs with a sense of native authenticity, while the pervasive African undertones lend a captivating rhythm and emotional depth. Furthermore, the reverence for Catholic saints in the lyrics reflects the historical and cultural impact of Christianity in shaping the artistic expression of the Brazilian people. Overall, these multifaceted influences converge to encapsulate the essence of Brazilian music, serving as a poignant reflection of the nation’s rich cultural heritage.

I bet some of you out there are wondering, “Well, that’s nice in theory and all but…

WHERE’S YOUR PROOF?”

Well…

There are some mestres who have gone to the country of angola in search of capoeira’s roots. Mestre Cobra Mansa of FICA has made this journey several times, and here’s 2 video clips of what he’s found there:

Click HERE if you would like to order a copy of the DVD of this documentary.

And, Here’s a modern demostration of engolo (N’golo) from Angola:

Notice the spin kicks, headbutts, hand slaps and sweeps in Engolo and evasions now called Esquiva in Capoeira. Now anyone can see that although this isn’t capoeira, but you can also see where some of the strikes and fighting strategies in capoeira may have come from.

And, check out what this Congolese Capoeirista has to say about Capoeira’s history:

And, click HERE to read this fascinating article, written by Edward L. Powe about his research about the origins of Capoeira, which you can find more info about on his website, www.blacfoundation.org. And also, listen to what he has to say about capoeira’s african origins below:

Now if you had a chance to look at that article, you’ll see that Mr. Powe mentioned in that article a martial art from the island of REUNION called MORINGUE. I’m not sure if he’s seen it or not, but with one quick You Tube search, you can find a number of videos showcasing this style.

Below, I made a small video playlist showing some of these videos.

..

Looks a lot like Capoeira, doesn’t it? Heck, in the 2nd video on the playlist above, you even see a BERIMBAU.

And, check out this video by T.J. Desch-Obi, where he talks about Capoeira Angola’s history.

Much of the information he talks about in this video he had written in his book, Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art Traditions in the Atlantic World (University of South Carolina Press, 2008), which you can order from AMAZON by clicking HERE.

And also, click HERE to watch his other video on VIMEO, where he talks more about this book, specifically about his experiences with Knocking and Kicking, and Engolo.

And also, click on the title below to read this article from VICE SPORTS:

Fighting the Shackles of Slavery: ‘Kicking and Knocking’ in the Antebellum South

And, one more thing.

Capoeira is not the ONLY surviving Afro-Atlantic martial art practiced in North and South America. It’s just the most well known…

But we’ll cover that on another PAGE.

So, now that I’ve given you what I believe was the origin of Capoeira, here’s a some aspects of brazilian history, and capoeira’s place in it.

SLAVERY, AND RESISTANCE

“Let me tell you all a little story about THE ENSLAVEMENT OF my people in Brazil… And how they fought back.”

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda ê

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda ê

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda á

Porque me trouxeram de Aruanda

Pra que me trouxeram de Aruanda

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda ê

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda ê

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda á

Porque me trouxeram de Aruanda

Pra que me trouxeram de Aruanda

Vim no navio de Aruanda, Aruanda ê

Now before I go on, I want to talk a bit on something that was touched upon in the above video that some of you may have missed, and that is this:

AFRICANS NEVER SOLD THEIR OWN PEOPLE AS SLAVES!!!

At first, I felt that I shouldn’t have to explain this to people because I thought it should have been obvious, but

AFRICA WAS NEVER A COUNTRY, IT IS A CONTINENT!!!

Africans were not selling “their own”, or “their fellow Africans”, they were selling their enemies, just as the Greeks and Romans once did. The continent we now call AFRICA, then as now, was made up of many different kingdoms, and empires. The inhabitants of those kingdoms were no more selling “their own” than, say, “Europeans” were killing “their own” during the Holocaust.

I say this because whenever the subject of slavery comes up, Some White folks (And People of color) usually tend to use the stock argument of,

“Well, Africans sold their own people as slaves”.

Its main purpose is to draw attention away from what the whites did by trying to turn the tables.

This part of the past makes many White people uncomfortable. But instead of facing up to it, they have built up defenses against it. Everything from…

“Well, all races have practiced slavery”

“Whites were the ones who stopped slavery”

“My family never owned slaves”

“Africans are still selling slaves“

“Blacks are better off in America than in Africa”

To my all-time favorite,

“Blacks were selling Blacks”.

People like to add this argument like it’s some kind of trump card, their “Ace in the hole”, so to speak, especially after you debunk the other arguments, since of course,

ALL AFRICANS ARE BLACK!

RIGHT?

RIGHT.

But have any of you ever wondered when black people became black, or, more importantly,why BLACK people became BLACK?

It’s crucial to understand the historical contexts and complexities of slavery, rather than simplifying it into a monolithic and uniform phenomenon. By acknowledging the diverse political, social, and economic dynamics prevalent in different African kingdoms and empires, we gain a more comprehensive perspective on the African slave trade. Furthermore, comparing the transatlantic slave trade to other historical atrocities highlights the need to approach the subject with nuance and sensitivity.

While discussions about slavery can be challenging, it’s essential to engage with empathy and an open mind. Acknowledging the various perspectives and experiences contributes to a more informed and constructive dialogue on this critical issue. It’s important to promote understanding and empathy, rather than perpetuating misconceptions and oversimplifications. This approach allows for a more nuanced and respectful discussion, paving the way for meaningful progress and mutual understanding.

The history of the transatlantic slave trade is a deeply somber and painful chapter in the shared human experience. The forced migration of millions of individuals from Africa to the Americas represents an unfathomable tragedy that has had profound and enduring effects on the social, cultural, and economic landscapes of both continents. The stories of resilience, endurance, and the relentless pursuit of freedom in the face of unimaginable suffering and adversity are a testament to the indomitable human spirit.

The harrowing journey across the Atlantic Ocean, often referred to as the Middle Passage, was marked by unspeakable cruelty, inhumanity, and loss. The sheer magnitude of human suffering endured during these voyages is beyond comprehension. Families were torn apart, communities were decimated, and the profound emotional and psychological wounds inflicted during this dark era continue to reverberate through generations.

It is essential to recognize and honor the resilience and strength of the African diaspora, whose enduring legacy is a testament to the power of the human will to overcome adversity and injustice. By acknowledging the profound suffering and injustices of the past, we can strive to create a more just, equitable, and compassionate world for future generations. The recognition of this painful history is crucial for fostering understanding, empathy, and meaningful reconciliation in our global society.

Oh, and don’t think I don’t know there was a WHITE SLAVE TRADE either.

Well anyway, it’s just something I wanted to get off my chest.

O.K., now back to capoeira.

The African slaves brought to Brazil belonged to three different groups, each contributing to the rich cultural tapestry of the country. The Sudanese group included people from the Yoruba and Dahomean peoples, who brought with them their unique traditions and beliefs. The Islamic Guinea-Sudanese groups, comprising the Males and Hausa peoples, also played a significant role in shaping the cultural landscape of Brazil. Additionally, the Bantu groups, including the Kongos, Kimbundas, and Kasanjes from Angola, Congo, and Mozambique, contributed to the diverse heritage of Brazil.

It is believed by some historians and scholars that it was the Bantu group from Angola that played a pivotal role in the development of what is now known as Capoeira. The influence of these diverse African groups is evident in various aspects of Brazilian culture, demonstrating the enduring impact of their contributions throughout history.

In its first century, the main economic activity in the colony was the production and processing of sugar cane. Portuguese colonists created large sugarcane farms called engenhos, which depended on the labor of slaves.

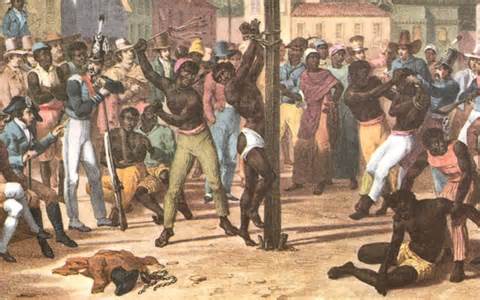

Slaves, living in inhumane conditions, were forced to work hard and often suffered physical punishment for small offenses. This brutal system perpetuated the suffering and exploitation of countless individuals, leaving a dark and haunting legacy that continues to impact societies to this day. The labor of these enslaved people not only fueled the colonial economy but also contributed to the immense wealth and power amassed by the European colonizers, highlighting the inherent cruelty and injustice of the system. Furthermore, the reliance on slave labor on sugar plantations was a fundamental aspect of the transatlantic slave trade, leading to the forced migration and dehumanization of millions of individuals. The enduring repercussions of this abhorrent practice serve as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted consequences of historical oppression and the ongoing struggle for societal justice and equality.

It was within this challenging environment, I strongly believe, that capoeira originated as a means of survival. It served as a vital tool that enabled an escaped slave, devoid of weapons or resources, to navigate and withstand the adversities of an unfamiliar and hostile terrain. This martial art provided a mechanism for confrontations with the formidable CAPITAES-DO-MATO, the heavily armed and mounted colonial enforcers tasked with pursuing and apprehending escapees.

Repouso entregue a um colchão de pedra

Incorporando o travesseiro a própria mão

Retratos da nova, cega vida escrava

Enfatizada a culpa da exploração

Esquecendo os erros do próprio passado

Ignorando a fome como obrigação

É só mais um truque, sujo e desumano

Procurando otimizar a produção

Disfarçando as correntes de um mundo novo

Aparentando um trabalho real

Enxutas opções aos que julgam bobos

desconhecida vida do próprio ancestral

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato ta chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato ta chegando aí

Tentando viver com um trabalho honesto

Acredita não ter outra opção

Vem se contentando com a comida de restos

Assinalando a auto-destruição

Quem tem pouco é sempre jogado pra baixo

Roubar dignidade virou tradição

Destruindo toda sua esperança

Depositada apenas na sua oração

Inexistente admissão do fato consumido

Falha do orgulho, mais um erro capital

Tornando a todos os seus próprios inimigos

Erguendo outra fronteira intelectual

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, ta chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, ta chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, ta chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, ta chegando aí

Pega no batente doze horas de trabalho

Tu fica na merda tudo lá é esculachado

Monta o teu barraco, no meio da fumaça

Aqui todo mundo fica junto e misturado

Mesmo sem vacilo tu já ta com a cara a tapa

E se der um pio ouve o grito da chibata

Bota lá no tronco, e deixa marcado

Que esse vacilão nunca mais vai agir errado

Manda o gato ir à caça trazer mais um rato

Cria o teu boçal pra viver sempre acuado

E se um brasileiro não aceita ser mal pago

Pega um estrangeiro e ameaça de deportar

Diz que eu tenho escolha e me fala de liberdade

Só que eu faço, pago e ainda passo necessidade

Quem fica por cima, manda de verdade

Desde de cedo ensina a ter preguiça de lutar

Inexistente admissão do fato consumido

Falha do orgulho, mais um erro capital

Tornando a todos os seus próprios inimigos

Erguendo outra fronteira intelectual

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, tá chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, tá chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, tá chegando aí

Avisa nos quilombos multicoloridos

Que o capitão do mato, tá chegando aí

Tá chegando, tá chegando

Tá chegando aí

Tá chegando, tá chegando

Tá chegando aí

Tá chegando aí

Rest delivered to a stone mattress

Incorporating the pillow by hand

Portraits of the new, blind slave life

Emphasized the guilt of exploitation

Forgetting past mistakes

Ignoring hunger as a must

It’s just another trick, dirty and inhumane

Seeking to optimize production

Disguising the chains of a new world

Looking like real work

Lean options for those who think they are fools

unknown life of own ancestor

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

Trying to live with an honest job

Believe you have no other option

He has been settling for leftover food

Signaling self-destruction

Those who have little are always thrown down

Stealing dignity has become a tradition

Destroying all your hope

Deposited only in your prayer

No admission of consumed fact

Failure of pride, yet another capital mistake

Making everyone your own enemy

Building another intellectual frontier

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is getting there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is getting there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is getting there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is getting there

Pick up twelve hours of work

You stay in the shit, everything there is carved

Set up your shack, in the middle of the smoke

Here everyone stays together and mixed

Even without hesitation, you already have your face slapped

And if you make a peep, you hear the scream of the whip

Put it in the trunk, and leave it marked

That this vacillator will never act wrong again

Send the cat to go hunting to bring another mouse

Create your mouth to always live cornered

And if a Brazilian does not accept being poorly paid

Takes a foreigner and threatens to deport

Says I have a choice and tells me about freedom

I just do it, pay it and still need it

Who is on top, really rules

From an early age teaches to be lazy to fight

No admission of consumed fact

Failure of pride, yet another capital mistake

Making everyone your own enemy

Building another intellectual frontier

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

Warns in the multicolored quilombos

That the captain of the bush is coming there

It’s coming, it’s coming

It’s getting there

It’s coming, it’s coming

It’s getting there

It’s getting there

Now, from the VERY BEGINNING, the slaves resisted. Even on some of the slave ships to the Americas, they RESISTED. The spirit of resistance among the enslaved people was pervasive and innate, stemming from a deep yearning for freedom and justice. It manifested in various forms, from small acts of defiance to organized rebellions, continually challenging the brutal system of slavery.

This unwavering determination to resist oppression symbolizes the enduring resilience and strength of the human spirit. The defiance of the enslaved individuals resonates as a testament to the universal longing for autonomy and dignity, transcending time and place, and inspiring hope for a better future.

Soon several groups of escaping slaves would gather and establish what were called QUILOMBOS, settlements in far and hard to reach places. The Quilombos were havens for those seeking freedom from the oppression of slavery, providing not only physical safety but also a sense of community and autonomy. These settlements were founded on principles of resilience, resistance, and solidarity, becoming symbols of hope and defiance in the face of adversity. The inhabitants of Quilombos developed unique cultural practices, blending African traditions with indigenous influences, creating vibrant and rich societies within the constraints of their remote locations. Despite facing constant threats from colonial authorities and slave hunters, the Quilombos stood as testament to the unwavering spirit of those who sought liberty and equality, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire and resonate to this day.

These quilombos often formed in remote and inaccessible regions, where the natural environment provided both protection and sustenance for the communities. They became spaces of resistance and refuge for those seeking freedom from the brutalities of the slave trade. Despite facing constant threats and attacks from colonial authorities, these settlements represented a powerful assertion of autonomy and resilience. Quilombos played a crucial role in the fight against oppression and continue to serve as enduring symbols of strength and defiance in the face of adversity.

“Have fun Negro, the Whites won’t come here. If they do, they will be hit by a cross.”

Everyday life in a quilombo would have offered freedom and the opportunity to revive traditional cultures away from colonial oppression. Some quilombos would soon increase in size, attracting more fugitive slaves, Brazilian natives and even Europeans escaping the law or Christian extremism. Some quilombos would grow to an enormous size, becoming independent multi-ethnic states.

The establishment and growth of quilombos represent a remarkable defiance of the oppressive colonial regime in Brazil. In these autonomous communities, the inhabitants found a sanctuary where they could embrace their heritage and express their cultural traditions without fear of persecution. The diverse influx of people, including fugitive slaves, indigenous Brazilians, and even Europeans seeking refuge, contributed to the vibrant tapestry of multi-ethnic states that some quilombos evolved into. The sheer scale and independence of these communities stand as a testament to the resilience and determination of those who sought freedom from the constraints of colonial rule.

Near Porto Calvo, Pernambuco, in northeastern Brazil, a group of forty slaves rebelled against their master, killed his employees, and burned the plantation house. Once freed, they fled and decided to seek a place where they could avoid recapture by the slave hunters. They headed to the mountains.

The rebellion near Porto Calvo is a remarkable historical event that sheds light on the resilience and bravery of oppressed individuals fighting for their freedom. The actions of the forty slaves, who took a stand against their master and the oppression they faced, carry significant historical and cultural weight. The decision to rebel, not only against their master but also to secure their freedom and safety by venturing towards the mountains, highlights their determination and unwavering spirit in the face of adversity. This courageous act of seeking refuge amidst the challenging terrain showcases the strength and fortitude of those who sought to break free from the chains of slavery. The bravery and determination displayed by these individuals serve as a poignant reminder of the enduring human spirit and the pursuit of liberty in the face of profound hardship.

The tale of their journey reaching what they believed to be a secure sanctuary is a true testament to the resilience and determination of those seeking freedom. In their search for safety, they stumbled upon an oasis of palm trees, a sight so abundant and promising that they christened the place “PALMARES”. This name would echo through history as it grew to become not only the largest but also the most renowned Quilombo. The significance of PALMARES lies not only in its physical size and prominence, but also in the spirit of resistance and solidarity that it embodied. It stood as a beacon of hope and defiance, a testament to the human spirit’s unwavering pursuit of liberty.

So, was Capoeira developed and practiced in the quilombos?

As I have mentioned, there is no evidence to suggest that capoeira in any form was either taught or practiced in the quilombos. However, it is believed that in Palmares, as well as in other quilombos, tribes that were strangers or enemies in Africa had united to fight for a common goal. This led to the formation of a new community with a very rich cultural mixture. In this new environment, it is plausible that they would have shared and learned their dances, rituals, religion, and games from each other. One possible result of this rich cultural fusion could have been an early form of Capoeira.

These communities were growing rapidly as more refugees arrived in these African nation-in-exiles. As a consequence, this growth would have started to worry the colonizers. People from these communities would come down from the mountains to trade produce, fruit, and animal skins, and would often raid plantations to free more slaves. Interestingly, in some parts, colonists developed positive trade relations with the people from the quilombos and were even opposed to their suppression, believing that peace with them was the only way of achieving stability. This historical context sheds light on the complex dynamics between the colonizers and the quilombos, adding depth to the understanding of this period of history.

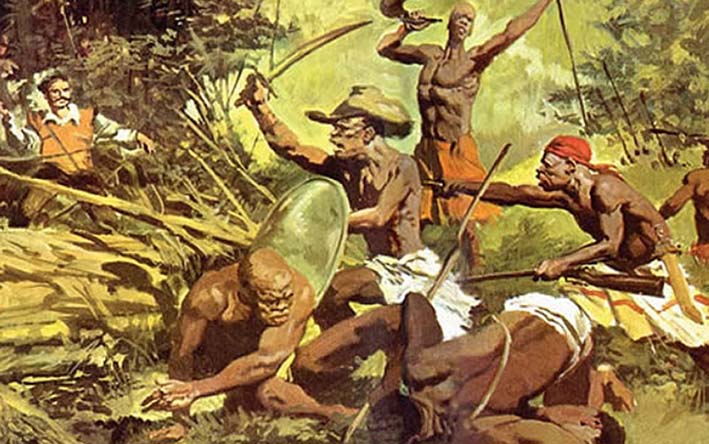

The expansion of quilombos in colonial Brazil had a significant impact, as the growth of these communities began to affect the plantations and the lives of the colonists. The increasing number of escaped slaves from the plantations led to a decrease in the labor force, causing economic hardships for some colonists. In response to the threat posed by the quilombos, the colonial government organized expeditions to dismantle these communities. These expeditions were comprised of experienced and well-armed soldiers who ventured into the jungles to confront the freed slaves. Despite the military prowess of the Portuguese soldiers, the quilombo inhabitants had developed a formidable system of jungle warfare and ambush tactics that posed a challenge to their attackers.

It is fascinating to consider the role of capoeira in these unexpected attacks. Capoeira, with its fast and deceptive movements, could have played a pivotal role in the resistance efforts of the freed slaves. The unique fighting technique of capoeira, characterized by fluid and unpredictable movements, likely enabled the former slaves to effectively defend themselves and cause considerable damage to the expeditions sent to capture them. The resilience and resourcefulness of the quilombo warriors, combined with the incorporation of capoeira into their defensive strategies, exemplify the ingenuity and determination of those fighting for their freedom.

Furthermore, the potential dissemination of capoeira within the plantations is a compelling aspect to consider. As returned slaves could have shared their knowledge of capoeira with others on the plantations, it is plausible that this art form found fertile ground to take root and spread further. This underscores the cultural and historical significance of capoeira as not only a symbol of resistance and liberation but also as a means of cultural diffusion within the complex social fabric of colonial Brazil.

Now remember, this is only speculation on my part. Things could have happened this way, or it could have been TOTALLY different.

Yes, as was explained in the above video, Palmares was a significant community that was unfortunately destroyed, alongside many other quilombos throughout Brazil. However, it’s important to note that the legacy of quilombos lives on and endures.

If you would like to buy a copy of this film, click HERE.

Despite the devastating impact of destruction, numerous quilombos continue to thrive across Brazil, serving as a testament to the resilience and strength of these communities. Their ongoing existence is a powerful reminder of the rich cultural heritage and traditions that persevered through adversity, contributing to the diverse tapestry of Brazil’s history and society.

Well, that’s the end of PART 1 of his story.

The first part of the story provides a solid foundation for understanding the roots of capoeira and its significance in Brazilian history. As we move on to PART 2, we can expect to delve into the intriguing expansion of this cultural practice in the bustling cities of 18th and 19th century Brazil. The narrative is likely to shed light on the socio-cultural dynamics that influenced the spread of capoeira during that period, offering readers a fascinating insight into how it evolved over time.

Furthermore, Part 2 promises to explore the practice of capoeira from the historical era covered all the way to the present day.

Well, as I understand it, anyway.

This continuation is anticipated to illustrate the transformation of capoeira as it adapted to changing social landscapes, and how it has persevered as a cherished aspect of Brazilian heritage. Readers can look forward to gaining a comprehensive understanding of how capoeira has endured through the centuries, embodying the resilience and spirit of the Brazilian people.