The martial art, dance, and cultural practice of Capoeira Angola, though frequently analyzed and appreciated primarily through the framework of Brazilian history and its social-cultural evolution, in fact, possesses profound, intricate, and often under-explored linkages to the foundational philosophical traditions, cosmological worldviews, and ritualistic practices of West and Central Africa. A meticulous, in-depth exploration of this transatlantic connection reveals that Capoeira Angola is far more than a simple syncretic survival or fusion of African movement and Brazilian adaptation; rather, it stands as a sophisticated, living embodiment and preservation of specific, complex philosophical concepts, ethical systems, and spiritual principles that were forcibly transported across the Atlantic Ocean during the harrowing period of the transatlantic slave trade.

This connection is not superficial, extending into the core elements of the art. For instance, the circular formation of the roda echoes the circular cosmology prevalent in many Kongo and West African belief systems, representing continuity, community, and the cyclical nature of time and life. The principles of duality and balance, crucial to the jogo (game) between two players, mirrors the metaphysical concepts found in various indigenous African epistemologies—such as the balance between light and dark, good and bad, or the living and the ancestors. Furthermore, the foundational musicality, provided by instruments like the berimbau (a modified musical bow with clear African antecedents) and the call-and-response singing, serves as a direct, unbroken thread connecting the enslaved peoples’ oral and musical traditions to their homelands. These elements combine to demonstrate that Capoeira Angola functions not just as a physical discipline but as a mobile, performative library of African cultural retention and philosophical resistance within the New World context.

The philosophical underpinnings manifest in several key aspects of Capoeira Angola:

1. The Concept of Mandinga and Spiritual Power

In Capoeira Angola, mandinga refers to the elusive, deceptive, and often spiritual cunning employed by a player (capoeirista) in the roda (the circle in which Capoeira is played). This concept is deeply resonant with West African and Bantu ideas of spiritual power, charisma, and the strategic use of knowledge. In many West African cultures, the term mandinga (or similar phonetic variations) is linked to the historical Mandinka people and the specialized knowledge they held, often encompassing herbalism, divination, and protective spiritual practices. The capoeirista who possesses great mandinga is not just a skilled fighter but one who can manipulate the energy, rhythm, and psychology of the roda—a manifestation of a deeper, often unseen, force.

2. The Embodiment of Kongo Cosmology and Movement

The profound connections between Capoeira Angola and the philosophical and cosmological models of Central Africa, particularly those of the Bakongo people, are essential for a holistic understanding of this complex art form. The Bakongo, who constituted a significant demographic among the enslaved Africans forcibly transported to Brazil, offer a powerful and profound framework for interpreting Capoeira Angola’s underlying structure, movement, and ritualistic components.

This interpretation transcends the common perception of Capoeira Angola as a mere martial dance or a game. Instead, it positions the practice as a living repository of Kongo spiritual and philosophical concepts, effectively transforming the roda (the circle in which capoeira is played) into a site of cosmological reenactment. Key Bakongo concepts such as Kala (the world of the living), Lufu (the transformation and transition through death), and Kuanda (the world of the ancestors and spirits) map onto the temporal and spatial dynamics of the roda.

The circular formation itself can be viewed as an embodiment of the Kongo cosmos, the Yowa cross or Kala sign, which represents the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The movements within the jogo (the game played by two participants inside the roda), particularly the low, grounded postures like aú (cartwheel), queda de quatro (four-point fall), and negativa (negative position), can be interpreted not only as defensive tactics but as symbolic journeys toward and interaction with the earth, the realm of the ancestors. Furthermore, the role of the mestre (master) and the specific musical instruments, especially the berimbau, function as ritual conduits, guiding the energy and narrative of the performance in a manner consistent with Bakongo religious specialists who mediate between the visible and invisible worlds. This deep, syncretic philosophical heritage is what imbues Capoeira Angola with its spiritual gravitas and sustained cultural resilience.

.

—–1. The N’kisi and the Roda: The Cosmogram and the Sacred Center

The circular formation of the roda (the ring where Capoeira is played) is not an arbitrary spatial arrangement; it mirrors the Kongo concept of the cyclical nature of time, life, death, and the cosmos, often represented by the Kala, or the Kongo Cosmogram. This four-pointed figure encapsulates the journey of the soul and the continuous regeneration of the world.

- Cyclical Time: The roda embodies this cyclical worldview, representing the continuous flow of the past, present, and future, with every game being a rebirth of the tradition. It is a portal where ancestors are invoked and the spiritual dimension is immediate.

- The Sacred Center: The very center of the roda acts as a potent, liminal ritual space. It is the point of entry and exit, the axis mundi where the players (the capoeiristas) negotiate power, movement, and spiritual presence. This focal point draws and concentrates energy—much like a Kongo n’kisi (a sacred object, shrine, or container for spiritual forces) serves as an anchor for the community’s ancestral and natural forces. The n’kisi mediates between the visible world (kuna yza) and the spiritual world (kuna mpémba); similarly, the roda mediates between the everyday world and the heightened, ritualistic world of the game.

- The Berimbau: The lead instrument, the berimbau, stands as the authoritative voice and spiritual conductor of the roda. Its single string and resonating gourd can be interpreted as a type of aural n’kisi, directing the flow of energy, regulating the tempo of the cycle, and setting the spiritual tone for the interactions within the ring.

—–2. The Ginga: The Embodiment of Flow and Philosophical Resistance

The foundational, rhythmic, rocking movement of Capoeira Angola, the ginga, is far more than a simple ready stance. While it functions practically as a dynamic martial posture, constantly shifting the body’s weight to evade attack and generate power for movement, its deeper significance is philosophical and cosmological.

- Fluidity and Non-Stasis: The ginga‘s constant, flowing, non-linear nature echoes the fluidity, balance, and constant negotiation with the spirit world that is central to the Kongo worldview. It is the movement of water and wind—elements that cannot be grasped or contained.

- The Refusal of Fixity: Philosophically, the ginga is a profound act of resistance. It is a physical refusal to accept stasis, rigidity, or defeat, embodying the will to survive and remain mentally and spiritually free even under extreme duress. It is a constant dialogue between groundedness and movement, action and anticipation. To ginga is to move in a manner that refuses to be pinned down, physically, socially, or ideologically, thereby symbolizing the enduring spirit of the enslaved who refused to be fully defined or destroyed by their captors.

- A Conversation with the Spirit World: Through the ginga, the capoeirista is constantly “in motion” with the ancestors and the forces of nature, utilizing subtle shifts and feints that are not only deceptive to an opponent but also serve as a kind of moving meditation or prayer, keeping the spirit engaged and alert.

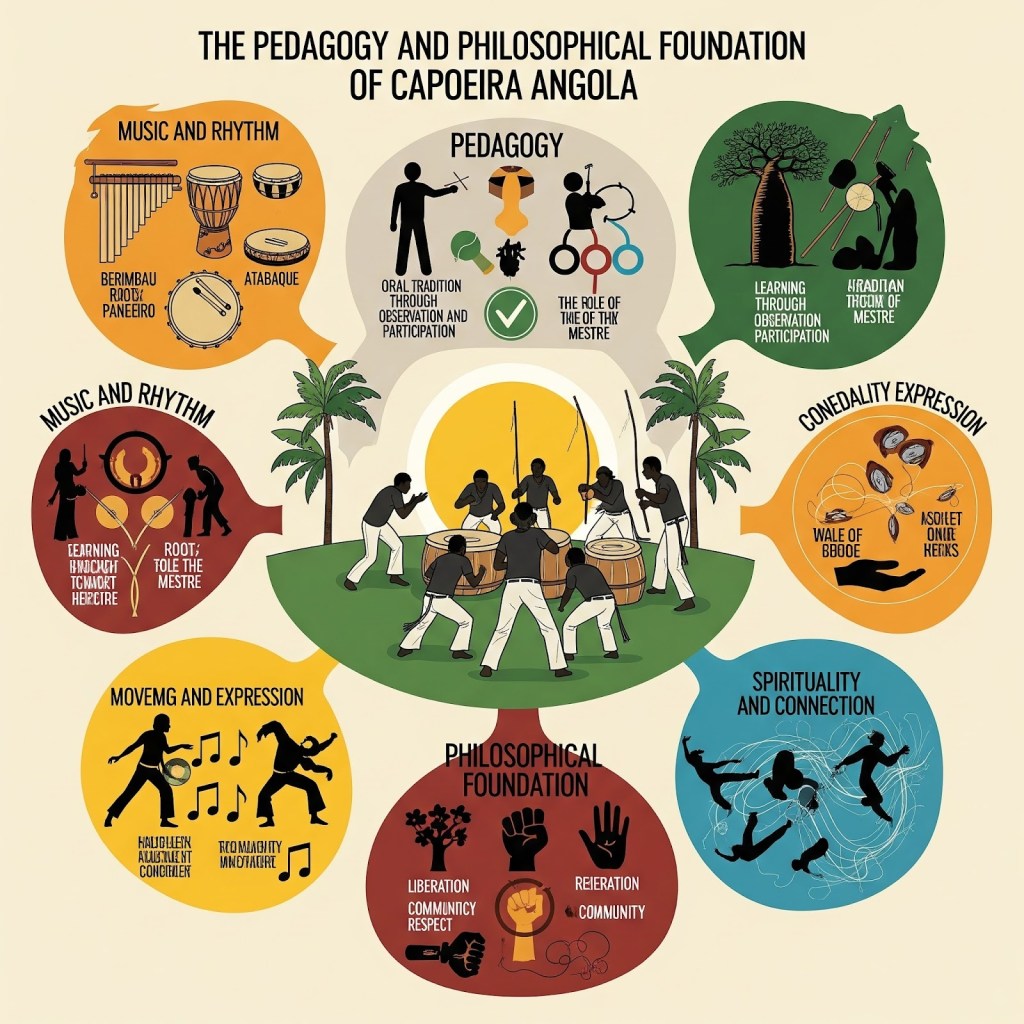

3. Oral Tradition, Music, and Communal Philosophy

The transmission of knowledge in Capoeira Angola is fundamentally an oral and experiential process, deeply rooted in the communal and performance-based pedagogical traditions of West and Central Africa. This educational model eschews reliance on written texts, prioritizing instead the direct, visceral transfer of wisdom. The core curriculum is preserved and disseminated through the artistry of its performance: through the call-and-response songs (corridos), the reflective, often historical solo narratives (ladainhas), and the practical wisdom contained in proverbs and traditional sayings.

At the heart of this pedagogy is the mestre (master), who serves not only as a technical instructor but as a philosophical and historical interpreter. The mestre‘s direct instruction—a blend of physical correction, metaphorical guidance, and practical demonstration—is the primary conduit for the ethical and strategic principles of the art. This structure ensures that wisdom is never abstract but always contextual, embedded in the rhythm of the game and the dynamics of the community. This method is a direct continuation of traditional African pedagogy, where spiritual, ethical, and survival wisdom is inseparable from communal participation, ritual, and musical performance.

The musical ensemble, or bateria, is not mere accompaniment; it is the spiritual and rhythmic architect of the roda (the circle in which Capoeira is played). Central to this ensemble is the berimbau—a single-string musical bow. More than an instrument, the berimbau is the spiritual heart and rhythmic command center of Capoeira. Its unique sound calls upon ancestral memory, setting the philosophical and energetic tone for the interaction. The subtle variations in its tempo, rhythm, and timbre dictate the speed, intensity, and strategic focus of the game being played. The interplay of instruments—including the atabaque (drum), pandeiro (tambourine), and reco-reco (scraper)—forms a complex linguistic layer, a non-verbal commentary on the game, understood and responded to by experienced players.

In essence, an analytical connection between Capoeira Angola and West African, specifically Kongo, philosophy reveals the art form as a profound, living tradition of embodied philosophy. It is a sophisticated, kinetic system where abstract philosophical tenets are not merely subjects for detached, academic debate or historical study but are instead actively performed, preserved, and internalized through the body’s movement, ritual, and communal structure. Capoeira Angola is a physical manifestation of a cultural worldview that survived the brutal ruptures of the transatlantic slave trade by being encoded into dance, music, and fight.

The core principles that define this philosophical nexus are continuously practiced and honed within the roda, the central circle where the game is played. Principles such as resilience (resistência) are not just conceptual ideals; they are learned through the sustained, low-to-the-ground movements and the necessity of returning to the base (aú, queda) after an attack. Strategic evasion, known through the interconnected concepts of malícia (cunning, street-smarts) and mandinga (spiritual, sometimes trickster-like power), represents a profound philosophical acceptance of asymmetry. The Capoeirista learns to triumph not through brute, confrontational force but through cleverness, timing, and psychological misdirection—a direct reflection of the survival tactics employed by enslaved Africans against an overwhelmingly powerful oppressor.

Furthermore, the spiritual power of music and sound is central to this embodied philosophy. The berimbau, the guiding instrument, acts as the “soul” of the roda, dictating the pace, energy, and spiritual quality of the game. The call-and-response songs (corridos) and the rhythmic drumming create a liminal space, an altered state of consciousness that connects the participants to their ancestors and the historical memory of struggle and resistance. Deep spiritual grounding, often connected to the Kongo concept of the cosmogram and the cyclical nature of existence, is reinforced by the circular structure of the roda itself, symbolizing the eternal return and the unbroken connection between the living, the dead, and the divine.

The non-linear, unpredictable movement of the Capoeirista—the fluid arcs, deceptive stops, and unexpected shifts in tempo—reflects a philosophical acceptance of life’s complex and often indirect path. This movement celebrates ingenuity and adaptability over rigid, predictable force. The physical practice, therefore, is far more than a martial art or a dance; it is a continuous, moving meditation on the core values of Afro-Brazilian and African cultural heritage. It is a dynamic, intergenerational pedagogy that teaches respect, community, perseverance, and the ultimate wisdom that true power lies in flexibility and the intelligence of the body. Capoeira Angola is, in this light, a powerful, living repository of African-diasporic epistemology.