The decision to employ lethal force is not merely a tactical choice; it is the most profound and consequential ethical, moral, and legal choice a person can make in a self-defense encounter. For a martial artist, whose training is inherently centered on the controlled, effective, and often philosophical application of force, this decision is uniquely fraught with additional complexity and increased scrutiny. This discussion significantly elaborates on the definition of lethal force and the critical legal principles that govern its use, paying special attention to the elevated responsibility carried by the trained defender.

—–I. The Gravity of Lethal Force: A Point of No Return

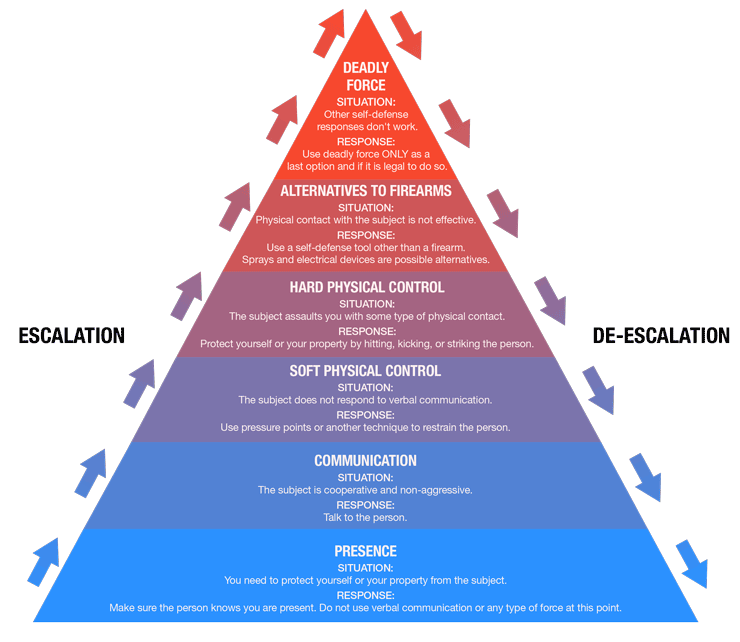

Lethal force, by its very definition, is any force that is reasonably likely to cause death or serious bodily harm. It represents the ultimate escalation and the final, irreversible act of self-defense. The moment of its deployment is truly a point of no return for all parties involved, and the weight of this responsibility rests heavily on any individual forced into such a situation.The Martial Artist’s Double-Edged Sword

For the martial artist, the burden is magnified. Their discipline often involves a deep philosophical commitment to the preservation of life and the avoidance of harm, yet their superior training provides the ability to end a confrontation quickly and decisively. This ability is a double-edged sword:

- Increased Capability: The martial artist possesses skills designed for efficient incapacitation, which means an action that might be considered non-lethal for an untrained person could be classified as lethal force when executed by a trained expert.

- Increased Scrutiny: This superior training simultaneously elevates the legal and moral scrutiny applied to their actions. The core principle of self-defense is not to eliminate a threat, but to stop the threat. A martial artist is held to a higher standard to continually demonstrate that their advanced skills were first employed to find a path toward neutralization with less-than-lethal means. The courts will ask: Could a person with this level of training have used a joint lock instead of a lethal blow?

Defining and Understanding Lethal Force Beyond the Firearm

Lethal force is a concept rooted in potential consequence, not necessarily the tool used. While a firearm is the clearest example, the definition is far broader:

- Contextual Weapons: Lethal force can be any object or action—including bare-hand techniques—that, in the context of the environment, the attacker’s condition, and the target area, is capable of causing death or grave injury.

- Specific Techniques: A precisely aimed strike to a vulnerable point (e.g., the temple or throat), a joint lock resulting in a severe, life-altering fracture, or the use of a common object (like a pen or coffee mug) as an improvised weapon can all be classified as lethal force.

- Legal Focus: The law focuses less on the tool (hand vs. knife) and more on the potential consequence and the intent of the user. Understanding this nuanced definition is critical, as a martial artist’s trained body is itself often considered a deadly weapon under the law, capable of meeting the threshold for “deadly force.”

—–II. The Critical Legal Principles Governing Use

The use of lethal force in self-defense is governed by strict, non-negotiable legal standards across most jurisdictions. These standards consistently revolve around the concepts of reasonableness and necessity. For a martial artist’s action to be deemed legally justifiable, a set of core principles must be met under the Objective Reasonable Person Standard.

A. Core Legal Principles of Justification

The following principles must be satisfied for the use of lethal force to be legally justified:1. Imminent Threat (The Temporal Requirement)

- Requirement: The defender must have a reasonable belief in an immediate and unavoidable danger of death or serious bodily harm to themselves or another person. The threat must be immediate and ongoing.

- Limitation: Lethal force cannot be used to preempt a future, non-imminent threat, nor can it be used as retaliation after a threat has passed. The moment the attacker retreats, is clearly disarmed, or is sufficiently incapacitated, the legal right to use lethal force generally ceases, as the threat is no longer imminent.

- Objectivity: Crucially, the danger does not need to be objectively real, so long as the belief was objectively reasonable under the circumstances. The “reasonable person” standard applies here: would a hypothetical, prudent person, placed in the exact same situation and possessing the same knowledge, have felt the threat was imminent?

2. Proportionality (The Force Requirement)

- Requirement: The force used must be strictly proportional to the threat faced. This is the critical barrier against excessive force.

- Limitation: Lethal force is only justified when facing a threat of death or serious bodily harm. Using lethal force to protect property (unless the theft involves an imminent threat of violence) or in response to a simple push or minor assault is nearly universally considered excessive and illegal.

- The Martial Artist’s Burden: A martial artist has a higher burden to prove that their superior skill set was used judiciously. They must demonstrate that the lethal response was truly the only proportional option left, having considered and discarded all reasonable, less-lethal alternatives.

3. Necessity (The “Last Resort” Standard)

- Requirement: Lethal force is typically justified only when all lesser means have failed or cannot reasonably be employed to stop the threat.

- The Proving Factor: The defender must prove that no reasonable, non-deadly alternative—such as verbal de-escalation, creating distance, or using non-lethal physical techniques (e.g., controlling a limb, pinning, or a non-damaging throw)—would have been sufficient to neutralize the immediate, imminent threat. Lethal force must be a true last resort.

4. Innocence/Standing (The Initial Aggressor Rule)

- Requirement: The person using deadly force must not be the initial aggressor or actively engaged in unlawful activity at the time of the incident. The law generally does not grant a person the right to provoke a deadly confrontation and then claim self-defense.

- Caveat: Even an initial aggressor may regain the right to self-defense if they clearly and explicitly attempt to withdraw from the conflict (e.g., turning and running, loudly declaring an end to the fight) and the original victim continues to escalate the confrontation with lethal force.

5. Reasonableness (The Objective Standard)

- The Overarching Principle: All actions are ultimately evaluated under the objective “reasonable person” standard. This standard is crucial during a subsequent criminal investigation or trial.

- Context of the Circumstances: The jury or judge must be convinced that a hypothetical person in the same situation, with the same knowledge, would have believed the force used was necessary to prevent imminent death or serious bodily injury. This includes the totality of the circumstances: lighting, distance, visibility, size and skill disparities, the attacker’s perceived capabilities, and the presence of third parties.

- The Trained Defender’s Context: For the martial artist, their specialized knowledge and training become part of the context the court considers. This context often leads to a higher expectation of control, restraint, and the ability to choose the most appropriate, least-harmful effective technique.

—–III. Key Legal Doctrines Affecting Lethal Force

The concept of “Necessity” is significantly influenced by state-specific legal doctrines that define whether a person has a legal obligation to disengage before fighting back with deadly force.

1. Duty to Retreat

- Definition: Historically, the common law required individuals to attempt to retreat from a confrontation if it was safely possible to do so before resorting to deadly force. This doctrine emphasizes that the preservation of life outweighs the right to stand one’s ground in public space.

- Status: Some states still impose this duty, requiring the defender to exhaust every reasonable and safe means of escape.

2. Stand-Your-Ground Laws

- Definition: Many states have enacted “stand-your-ground” laws that explicitly remove the duty to retreat.

- Application: These laws generally allow individuals to use deadly force in any location they are lawfully present if they reasonably believe it is necessary to defend against a deadly threat, without first trying to disengage. It essentially codifies the belief that a person has the right to meet a deadly threat with deadly force without incurring criminal liability for failing to run away.

3. The Castle Doctrine

- Definition: This principle is recognized in all states and focuses specifically on defense within one’s home (the “castle”). It generally allows homeowners to use deadly force against an unlawful intruder in their home without a duty to retreat.

- Presumption: A key feature is that the doctrine often includes a legal presumption that the homeowner had a reasonable fear of imminent death or serious bodily harm upon an unlawful, forcible entry. This presumption significantly aids the defender in meeting the Imminent Threat requirement.

- Limitation: This legal protection does not extend to the defense of property alone unless the threat to property also poses an imminent threat to the life or safety of the occupants.

In conclusion, for the martial artist, the path to justified use of lethal force is narrow. It requires not only superior physical skill but superior legal and ethical judgment, demanding proof that their actions met the objective standards of imminence, proportionality, necessity, innocence, and overall reasonableness in the face of a terrifying, life-or-death confrontation.

—–The Martial Artist’s Context

The Ethical and Legal Crossroads of Lethal Force in Martial Arts

When a Martial Artist Has to Use Lethal Force

For the purpose of this article, the discussion will reference the specific martial arts of Capoeira Angola, Didya Kabwaranan (a form of escrima from the northern Philippines), and Esgrima de Machete y Bordon (an Afro-Columbian martial art from the Cauca Valley in columbia). Why these systems? Because those are the specific systems I am currently studying, and the analysis is grounded in the principles and weapon dynamics inherent to them. However, the core message transcends these specific disciplines.

The principles and techniques learned in any martial art—whether focused on striking like Karate or Muay Thai, grappling like Judo or Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, or weapons-based systems like Kali or Kenjutsu—must be viewed through the lens of legal and ethical restraint when considering lethal force. This is a critical distinction, separating the pursuit of technical mastery from the profound responsibility that comes with possessing potentially deadly skills. A martial artist must understand that their hands, feet, or training implements are not merely tools for competition or self-improvement; they are, in a self-defense scenario, potentially lethal weapons.

The dojo, the roda (in Capoeira), or the training hall for Filipino martial arts practice, is a strictly controlled environment. It is a place governed by rules of courtesy, mutual respect, and pre-arranged boundaries designed to ensure the safety of all participants. The context is one of learning and structured sparring. The street, however, is not a controlled environment. When faced with a genuine threat to life or grievous bodily harm, the rules of engagement are no longer dictated by the traditions of competition or the etiquette of practice, but by the stark, unyielding principles of law and morality.

The martial artist, when confronted with a situation demanding the application of their skills, faces a profound ethical and legal dilemma. The transition from the controlled environment of the dojo or training hall to a real-world violent encounter is not merely a physical shift but a demanding mental and ethical pivot.

A technique that is considered technically perfect or a standard countermeasure in a controlled sparring session may instantly be deemed excessive and illegal force in a street altercation. The legal landscape is unforgiving, anchored by the strict standard of “reasonable force.” This is a high and constantly scrutinized bar, meaning the force used must be proportional to the threat faced and absolutely necessary to stop the harm.

The martial artist, therefore, has a dual and continuous responsibility:

- Mental and Strategic Training: They must constantly train their mind to prioritize de-escalation, strategic evasion, and escape. Their first goal is to avoid the confrontation entirely. If avoidance fails, they must employ the minimum necessary application of force—a soft block, a controlling joint lock, a push—before ever contemplating a technique that carries the inherent risk of death, permanent injury, or catastrophic life-altering consequences for the attacker.

- Ethical Responsibility: The mastery of a martial art does not function as a license for violence or an excuse to dominate. Instead, it imposes a far greater burden of responsibility. The trained individual possesses the knowledge and ability to inflict grave harm, and with that capability comes the duty to act with measured judgment and profound restraint. Every application of force must be a last resort, driven by necessity and self-preservation, not by ego or the desire to demonstrate skill.

The ultimate and singular goal of the trained martial artist in any real-world confrontation is survival and the preservation of life—their own, and if possible, that of others. The confrontation is not a performance or a test of skill; it is a desperate fight for safety that must be terminated the moment the threat is neutralized, demonstrating an ethical discipline that transcends mere physical prowess. The true measure of their mastery lies not in their ability to fight, but in their wisdom to avoid it, and their restraint when fighting becomes unavoidable.

The Life-Altering Calculus

As we delve into the decision of whether to use lethal force or not, it is paramount to remember that your decision to use lethal force may have consequences, and, the decision to not use lethal force may also have consequences. The stark reality is that martial artists, especially those training in systems designed for real-world conflict or weapons use, are forced to consider this “life-altering calculus” in a moment of extreme duress.

The Multifaceted Consequences of Employing Lethal Force

The decision to employ lethal force—even in a context of self-defense—initiates a cascade of immediate and long-term repercussions that extend far beyond the immediate physical confrontation. This choice, often made in a split second under extreme duress, subjects the martial artist to profound scrutiny across legal, civil, psychological, and moral domains.I. Legal and Judicial Accountability

The most immediate and harrowing consequence is the initiation of legal prosecution. The law is unyielding in its examination of the use of deadly force, requiring the martial artist to justify their actions under the stringent standards of criminal law.

- Criminal Law Scrutiny: The central legal test hinges on the “reasonable belief” standard. The defender must convincingly demonstrate that they had a genuine and rational fear of imminent death or serious bodily harm at the precise moment force was applied. This scrutiny is detailed, involving an examination of the threat’s nature, the defender’s actions, and the proportionality of the force used. A failure to satisfy a jury of this reasonable belief—even if the threat was real—can lead to criminal charges ranging from manslaughter to murder.

- The Burden of Proof: Unlike many other crimes, self-defense places a significant practical burden on the defendant to prove their state of mind and the necessity of their actions, often against the backdrop of a system that views the taking of a life as the ultimate transgression.

II. Civil and Financial Liability

Regardless of the outcome in the criminal courts—even if the defender is fully acquitted—they remain vulnerable to civil liability.

- Wrongful Death Suits: The survivor or family of the assailant retains the right to sue the martial artist for wrongful death in a civil court. The burden of proof in civil court is significantly lower than in criminal court (a “preponderance of the evidence” rather than “beyond a reasonable doubt”). This means the martial artist could be found not guilty in the criminal sphere but simultaneously found liable in the civil sphere, resulting in substantial financial damages awarded to the assailant’s family.

- Financial Ruin: The cost of mounting both a criminal defense and a subsequent civil defense can be financially devastating, often leading to bankruptcy even if the defender ultimately prevails in court. The legal process itself becomes a protracted form of punishment.

III. Psychological and Emotional Trauma

Crucially, the non-legal consequences often prove the most enduring and debilitating, affecting the martial artist’s mental health long after the courtroom proceedings have concluded.

- Profound Psychological Trauma: The act of taking a human life, regardless of justification, is a fundamentally traumatic experience. This can manifest immediately or develop over time.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): The hyper-vigilance, flashbacks, emotional numbing, and avoidance behaviors characteristic of PTSD are common among individuals forced to use lethal force. They may find themselves unable to participate in their art or even normal life, haunted by the memory of the event.

- The Heavy Moral Burden: This is the internal reckoning that no court can judge. The moral burden of having taken a human life is immense. The legal system seeks to determine justification—was the act permissible? The ethical and personal system demands a reckoning with the act itself—was the act necessary, and what does it cost to carry that memory? For a martial artist whose philosophy is often centered on preservation and control, this contradiction can lead to intense guilt, self-doubt, and a complete re-evaluation of their life’s principles.

The Profound Moral and Psychological Burden of Lethal Force Decisions

The consideration of using lethal force is perhaps the single most terrifying and complex ethical dilemma a martial artist or any trained defender will ever face. The consequences of the decision—whether to act or to restrain—are equally life-altering, albeit through different channels of trauma and guilt.

The Consequences of Not Using Lethal Force: The Trauma of Failure

Conversely, the decision to hold back, to consciously prioritize restraint when lethal force is truly and objectively warranted by the threat level, may lead to an equally tragic, and in some ways, more enduring outcome. This choice—the choice to hesitate or to use insufficient force—can directly result in the death or catastrophic, permanent injury—not only to the martial artist themselves, but potentially and most agonizingly, to innocent third parties under their protection, such as family members, clients, or bystanders.

This latter outcome leaves a different, yet equally severe, form of psychological scarring: the pervasive, corrosive guilt and trauma associated with the perceived and actual failure to act decisively enough to protect life. The martial artist is left to wrestle with the eternal, inescapable question: Could I have prevented this? This trauma is often compounded by the public and legal scrutiny that follows an avoidable death or injury, where the narrative focuses on inaction rather than the threat that necessitated the ultimate defense. The guilt stems from the belief that they possessed the capability, the training, and the moment, but chose a path that led to loss.

The Inescapable Calculus and the Role of Training

The choice in that split-second moment is a life-altering, binary calculus with no comfortable middle ground and certainly no easy answer. It requires a nearly instantaneous, simultaneous assessment of multiple critical factors:

- Immediacy and Severity of the Threat: Is the threat genuine, immediate, and capable of inflicting death or grievous bodily harm?

- Capability: Do I possess the physical and mental ability to execute the necessary force without failure?

- Legal Justification: Does the level of force meet the stringent legal standard of self-defense for that jurisdiction?

- Moral and Conscience Bounds: Can I live with the outcome, even if legally justified?

This assessment must be performed under the most terrifying, adrenaline-fueled, and chaotic circumstances imaginable. Therefore, the essential goal of advanced training is not merely to instill the technical skills to prevail in a confrontation. More fundamentally, the training must embed an unshakable core of wisdom, situational awareness, and disciplined judgment to know when and how to apply those skills. This wisdom must operate within the strict ethical boundaries of conscience and, critically, within the binding legal parameters of necessary and proportionate force. The martial artist must be trained to recognize the line—the point of no return—and possess the clarity of mind to cross it decisively, or to consciously remain behind it, knowing the profound gravity of either action.

In Conclusion: The Martial Artist’s Ultimate Dilemma

The journey of a martial artist is fundamentally about self-mastery, discipline, and the pursuit of peaceful resolution. They train not to inflict harm, but to prevent it—to be a shield, not a sword. This philosophy forms the bedrock of their practice, making the prospect of lethal force the ultimate moral and ethical crucible.

When Lethal Force is the Only Resort

The phrase “lethal force is the only resort” represents the absolute breaking point, a devastating moment where all other options—de-escalation, disengagement, non-lethal submission, or incapacitation—have failed or are rendered impossible by the imminent threat.

For the trained martial artist, the contemplation and potential application of lethal force transcends the simple desire for victory or the mere demonstration of skill. It is an utterly desperate choice, a moment where a lifetime of discipline and training is confronted by the grim necessity of survival—the stark imperative to protect one’s own life or that of an innocent third party.

This ultimate defensive act is not a triumph; it is, fundamentally, a profound tragedy. It signifies the complete failure of the situation to be resolved through non-violent means. It is the failure of dialogue, the failure of de-escalation, and, in a wider lens, the tragic failure of societal safeguards. The martial artist, having exhausted every reasonable, lesser option—from tactical retreat to non-lethal compliance and incapacitation—is backed into a corner where force of a final nature becomes the only remaining shield.

The decision to use lethal force is never taken lightly. It is a terrifying burden, a weight that settles deep within the individual and is carried long after the immediate danger has vanished. This decision demands not just physical readiness, but an absolute mastery of self-defense law, a rigorous ethical responsibility, and an unflinching respect for the sacred, irreplaceable value of human life. The trained martial artist is acutely aware that their actions must be both necessary and proportional to the threat.

The encounter, often erupting from the mundane into sudden, terrifying violence, becomes the ultimate crucible for the martial artist—a moment where their entire life’s dedication is reduced to the stark, chaotic finality of a life-or-death confrontation. This is where their philosophy, their rigorous ethical code, their comprehensive physical prowess, and their legal knowledge are not abstract concepts, but immediate tools for survival.

The martial artist’s readiness is fundamentally proactive, yet its application is purely defensive. It is not about seeking conflict, but about possessing the skill, the clarity of mind, and the robust moral framework to decisively survive a conflict unjustly thrust upon them. Years of training instill the reflex not just to fight, but to de-escalate, to seek the escape route, and to use force only as a last, absolutely necessary resort.

The decision to cross that final, terrible threshold—the use of lethal force—is the most profound and devastating choice a person can make. It is a moment of total moral weight. The goal is to ensure that if this inescapable act is performed, it is done with a clear conscience, resting on the unshakeable pillars of self-preservation, justified necessity, and strict adherence to the bounds of justice and the law. This is the difference between a fighter and a martial artist: the fighter reacts; the martial artist survives and lives with the consequences, knowing they acted not out of malice or anger, but out of an ethical imperative to protect life when all other options were exhausted.