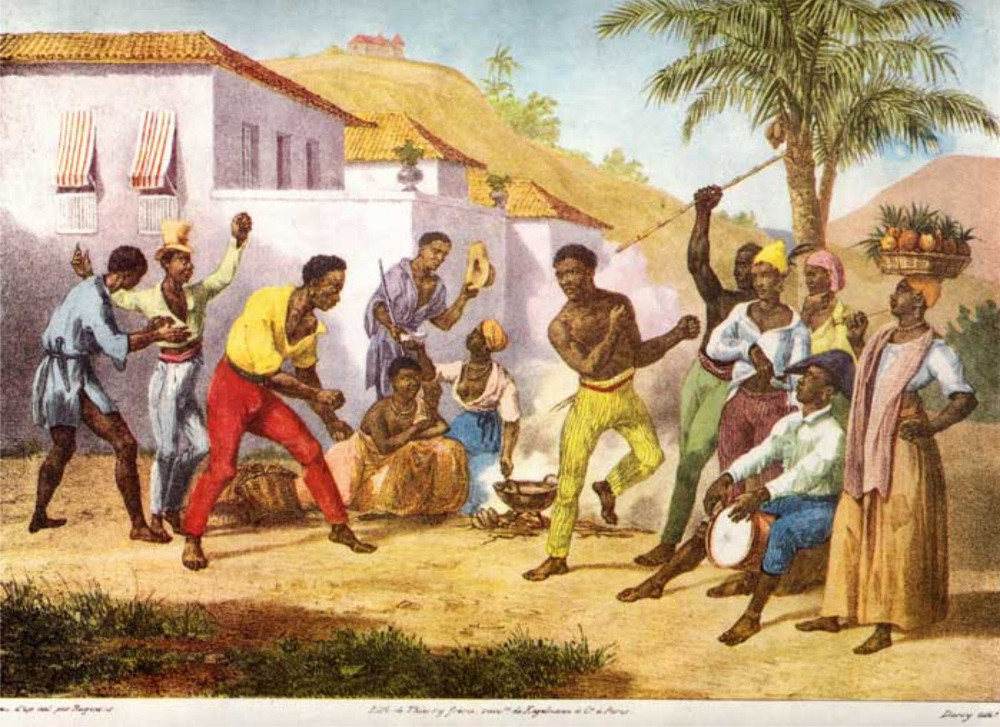

“The Negroes also have another war game, much more violent, the ‘jogar capoera’: two champions charge against each other, and seek to hit with their head the chest of the opponent they want to throw to the ground. By jumps on the side, or equally skilful parries they escape from the attack; but by throwing themselves against each other, more or less like he-goats, they sometimes get badly hurt at the head: therefore one sees often the jesting being displaced by fury, to the point that blows and even knives stain the game with blood” – Johann Moritz Rugendas

Hello Everyone, this is Part 2 of my history of Capoeira Angola.

I’m gonna pick up this part of the story in the 19th century, and continue till the present day.

But first, I want you to watch this video by T.J. Desch Obi.

Yes, I realize that Dr. Obi goes through the same topics as in the video about him that I posted on the 1st HISTORY PAGE, but what he said here on this video has much to do with this page.

While he may touch upon similar topics in different instances, the specific insights shared in this particular video hold significant relevance to the subject matter at hand. Each instance contributes unique perspectives and adds depth to our understanding of the historical context. Therefore, it’s worth integrating the distinct points made by Dr. Obi into our analysis on this page, as they enrich the overall discussion and offer valuable insights.

So, here we go.

Registries of capoeira practices existed since the 18th century in Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife. Due to city growth, more slaves were brought to cities and the increase in social life in the cities made capoeira more prominent and allowed it to be taught and practiced among more people. Because capoeira was often used against the colonial guard, in Rio the colonial government tried to suppress it and established severe physical punishments to its practice. The Calabouço prison, located in a military installation at the bottom of the Castelo hill in front of Guanabara bay, was the landing place for any slave that misbehaved or was thought to have misbehaved. As per an agreement between the State and the slave owners, any slave could be brought there to receive a “corrective whipping” of 100 lashes for the price of 160 réis. In 1808, King Dom Joao VI and his court fleeing Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Portugal arrived in Brazil. African culture among the slave population was persecuted and nominally banned under his rule. He believed that by destroying their cultural identity and taking away their sense of community, he could rule them more effectively. This effort to stamp out African cultural expression was, of course, detrimental to Capoeira. This attitude prevailed even after King Dom Joao left Brazil after Napoleon’s defeat, and even during the successive reigns of Pedro I (self-crowned Emperor of Brazil 1822) or Pedro II (crowned in 1831 after his father’s abdication).

African culture as a whole, and Capoeira along with it, was frowned upon and for the most part banned. Some believe that it was at this time, in order to overcome this law; the slaves disguised their fighting style as a dance so that the plantation owners would be completely oblivious to the fact that the slaves were actually training for combat.

However, it’s hard to believe that is the case because, if all forms of cultural expressions by the Africans were outlawed, then why would the plantation owners tolerate the dancing that disguised Capoeira?

The rich history of capoeira is a narrative brimming with instances of profound heroism and remarkable bravery, fundamentally shaping its legacy. A particularly notable example of this valor is woven into the tumultuous events of the early 19th century. During the unrest surrounding the Rio de Prata war, a substantial contingent of capoeiristas in Rio de Janeiro emerged as key figures in a critical military confrontation. Their collective action in 1828 was instrumental in quashing a serious rebellion instigated by foreign soldiers who were causing significant disruption in the city.

The capoeiristas, practitioners of this unique Afro-Brazilian martial art, distinguished themselves not merely through their exceptional physical prowess, but more profoundly through the singular and effective application of their martial skills in a real-world conflict. Their contribution was particularly noteworthy during the suppression of the 1828 rebellion.

The core of their combat effectiveness lay in their signature agility, a style characterized by a mesmerizing blend of fluid, almost dance-like movements and dynamic acrobatics. This unconventional method, often underestimated by those unfamiliar with the discipline, was deliberately cultivated as a survival mechanism against an oppressive system. It was this fluidity, coupled with their remarkable speed and precision in striking and evasion, that allowed them to engage the mutineers with devastating effect. They were able to disorient and confuse opponents accustomed to more rigid, European-style military formations and tactics, transforming the battlefield into a theater where conventional defense was largely ineffective.

Developed in the shadows of a harsh, restrictive society, this fighting style proved to be a formidable and decisively disruptive force against the organized chaos of the rebellion. The successful and often pivotal intervention of the capoeiristas contributed significantly to the swift resolution of this major historical event, an intervention that was critical in preventing what could have escalated into further widespread chaos and prolonged bloodshed across the region.

As a direct consequence of their valor and impact, the capoeiristas who participated in the suppression of the 1828 rebellion received official recognition that transcended their marginalized social status. They were not only hailed as national patriots but also celebrated as true heroes. This public and institutional acknowledgment served as a powerful testament to the potent impact their unique art form and unwavering courage had on the historical trajectory of the fledgling nation. Their actions on the field of battle effectively solidified a place of respect, admiration, and even awe for the discipline of Capoeira in the collective historical and cultural memory, moving it from the periphery to a recognized, albeit still complex, element of national identity and defense.

Furthermore, the Paraguayan War from 1864 to 1870 saw the deployment of numerous capoeiristas to the front lines. Their participation and valor in this conflict earned them rightful recognition and reverence. This particular episode remains commemorated and cherished in a famous capoeira song that reverberates the spirit and resilience of these remarkable individuals.

The War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870), also known internationally as the Paraguayan War or the Great War in the Southern Cone, remains one of the most brutal, extensive, and profoundly transformative conflicts in the history of South America. Brazil, alongside its allies Argentina and Uruguay, found itself engaged in a prolonged and costly struggle against the Republic of Paraguay. To prosecute this massive war effort, the Empire of Brazil was compelled to mobilize an immense military force, drawing from all segments of its society. It was within the ranks of this colossal mobilization that a unique, vital, and highly recognizable group of soldiers emerged: the “Zuavos.”

The Distinctive Identity of the Zuavos

The term “Zuavos” (derived directly from the French Zouaves) was more than just a name; it was a distinguished honorific bestowed upon certain Brazilian volunteer and regular infantry units. These units consciously adopted the visually distinctive and historically resonant North African-inspired uniforms that had been popularized by the elite French Zouave regiments in the mid-19th century. This attire was instantly recognizable on the chaotic battlefields, characterized by its practical yet flamboyant elements: baggy, often vibrant red, trousers (sarouel), a short, embroidered jacket (veste), a vest (gilet), and the iconic, tassel-adorned felt fez cap (chechia).

Crucially, for the Brazilian Empire’s army, this colorful uniform masked a profound and complex socio-racial reality: the Zuavos were overwhelmingly composed of Afro-Brazilian soldiers. This demographic included a significant number of freedmen, or libertos, who volunteered or were conscripted, as well as slaves recruited into military service. For the enslaved, military service was often offered under the explicit, life-changing promise of manumission—personal freedom—upon their honorable discharge after the conflict’s conclusion. This promise of liberty provided a powerful, highly personal motivation for the tenacity these units would later demonstrate in combat.Indispensable Assets on the Battlefield

The Afro-Brazilian Zuavo units were not merely symbolic; they proved to be indispensable assets on the grueling battlefields of the Paraguayan War (War of the Triple Alliance, 1864–1870). These soldiers, frequently fighting under extreme duress—facing not only the enemy but also the devastating effects of disease, harsh climate, and logistical shortages—consistently delivered exceptional service. They demonstrated a level of commitment, loyalty, and fierce determination that often went well beyond the call of duty.

Their integration into the Exército Brasileiro and the subsequent operational reliance placed upon them by military command was a direct, yet often unacknowledged, consequence of the conflict’s staggering human cost. To maintain troop strength and meet the high quotas demanded by the protracted war, which were often enforced through widespread conscription and controversial recruitment methods, Brazil was compelled to rely heavily on its vast non-white population. This demographic constituted the very backbone of the nation’s labor force, yet was now thrust into the role of national defenders.

These distinguished units played a vital, and frequently heroic, role in the protracted and bloody fighting that characterized the war’s most critical phases. Their contributions were particularly notable in major engagements where Brazilian success was far from guaranteed and the fighting was most intense. They distinguished themselves through exceptional bravery, tenacity, and resilience in key battles, including the decisive and blood-soaked Battle of Tuyutí (May 1866), the prolonged and grueling Siege of Humaitá (1868), and the intense, final-phase actions at Lomas Valentinas (December 1868). Their performance in these severe engagements solidified their reputation as some of the most reliable, determined, and effective soldiers in the imperial service. Special battalions, such as the famed Batalhão de Voluntários da Pátria (Volunteers of the Fatherland), were heavily populated by these highly motivated soldiers.The Paradox of Service and the Path to Freedom

For many of the Afro-Brazilians, joining the Zuavos and similar volunteer corps was a high-stakes gamble. They were fighting not merely for the geopolitical goals of the Empire of Brazil, but for a tangible, deeply personal, and life-changing reward: their personal freedom and the promise of a more equitable place in society upon their eventual return. This powerful motivation for self-emancipation often fueled the exceptional ferocity, combat resolve, and individual acts of valor they displayed. Their service, therefore, represents a critical intersection of military history, the institution of slavery, and the complex path toward full citizenship in 19th-century Brazil.

The service and sacrifice of these soldiers constitute a deeply complex and paradoxical chapter in Brazilian history. Their willingness to fight underscores the inherent contradiction of a black man fighting and dying for the preservation and victory of an empire that still sanctioned and profited from the institution of slavery. The image of a black man in a Zouave uniform, giving his life for his country’s flag while his family might remain in bondage, is a powerful historical testament to the era’s social injustices.

Their military participation was undeniably instrumental and ultimately indispensable to the victory of the Triple Alliance. However, despite their valorous service, the blood they shed, and the promises made, the ideals of equality, social mobility, and recognition often remained tragically elusive for many upon their difficult return from the devastating battlefields of Paraguay. They had earned their freedom or distinction through blood, yet often came home to a society still stubbornly resistant to true racial and economic integration.

The indelible mark left by these Afro-Brazilian soldiers, armed not only with military weapons but often also with the formidable, often misunderstood, martial art of capoeira, continues to resonate. Their story, particularly as part of the Zuavos, is not merely a military footnote, but a vivid illustration of how marginalized groups can rise to define an era, their actions etching a permanent, inspiring narrative of self-determination, resilience, and heroic achievement into the collective memory of a nation.

The legacy of these capoeiristas as heroes and their indelible mark on history continue to inspire and resonate to this day, serving as a testament to the power of courage, skill, and unity in the face of adversity.

The post-war period in Rio de Janeiro witnessed a significant social transformation as veterans reintegrated into civilian life, navigating the complexities of their new roles in society. The emergence of these “maltas” groups, often formed by returning soldiers who sought camaraderie and solidarity, captured the public’s imagination and became an emblematic feature of urban life. These groups not only provided a sense of belonging but also served as platforms for social exchange, cultural expression, and political activism, forging connections among diverse communities with shared experiences.

These groups were far more than simple street gangs. They were highly structured, organized associations, central to the social and political undercurrents of the Imperial capital. Their membership was predominantly composed of capoeiristas—master practitioners of capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian martial art, dance, and cultural practice. The Maltas became an essential, albeit often feared, component of the city’s popular culture and power dynamics.

Their influence extended beyond mere presence, shaping the cultural and social fabric of the city, with vibrant gatherings, parades, and local festivals that celebrated their contributions and fostered a renewed sense of identity. As a result, the impact of these organizations reverberates through Brazilian history, underscoring their enduring significance in the tapestry of urban life, and highlighting how they helped to redefine notions of community, resilience, and national pride in the backdrop of a rapidly changing society.

The members of these “gangs” were known for their distinctive attire: they would don white clothing, bell-bottom trousers, a linen suit or shirt paired with pointed shoes, and often adorned their necks with a silk handkerchief, which doubled as protection against razor cuts (as a razor blade typically does not cut silk but instead gets impeded by it). Additionally, they would wear a hat and carry a weapon such as a knife, razor, or cane, prepared for any unexpected confrontations or situations that might arise. These Capoeiristas thrived in the city alongside an eclectic mix of individuals including prostitutes, aristocrats, immigrants, and intellectuals. They were drawn to parties, gatherings, and crowded spaces where they would engage in activities such as theft, looting, or conflicts with rival groups. When confronted by the police, they would often manage to evade capture; however, in cases where fleeing was not an option, they would not hesitate to engage in altercations with the authorities, often leaving them incapacitated or worse.

The 19th-Century Maltas: Street Battles, Political Ties, and Cultural Amalgamation

The bustling, rapidly modernizing streets of 19th-century Rio de Janeiro were often the stage for the intense rivalries of the Maltas, powerful, quasi-military street groups that dominated the social and political undercurrents of the era. Among the most legendary were the Maltas de Nagoas and the Maltas de Guaiamuns. The Nagoas, typically associated with the gritty, hillside area of Lapa, and the Guaiamuns, rooted in the central district of Saúde, were locked in a perpetual struggle for local hegemony. These rivalries were far from mere squabbles; they escalated into notorious street battles that frequently paralyzed major thoroughfares, acting as a raw, albeit violent, form of social arbitration that determined territorial boundaries and established the pecking order within the city’s complex social hierarchy.

—–The Guaiamuns: A Study in Resilience and Political Integration

The Guaiamuns emerged as a particularly fascinating and influential organization. Their primary sphere of influence was the central region known as Cidade Nova (the new city), a hub of diverse populations and emerging political activity. Unlike simple street gangs, the Guaiamuns were deeply enmeshed in the city’s political landscape, maintaining intricate and vital connections to the Republicans of the Liberal Party. This political alignment significantly amplified their influence, granting them a degree of protection and operational scope that distinguished them from other groups.

Their internal composition was a vibrant testament to the era’s societal flux. The Guaiamuns were an incredibly inclusive and syncretic community, successfully assimilating a diverse array of people: recent immigrants seeking a foothold in the new world, native Creoles with deep roots in the city, free men carving out new identities, and even local intellectuals drawn to their organization and defiance of the established order. This cultural amalgamation resulted in a truly vibrant and multifaceted community, a microcosm of the dynamic forces reshaping Rio de Janeiro.Visual Identity and Ethos

The visual representation of the Guaiamuns was as distinctive as their composition. Their attire was a deliberate and potent symbol of their unique identity and collective ethos. Most notably, they donned a characteristic hat adorned with a striking red ribbon tied over a field of white, positioned prominently on the front and back flaps. This sartorial choice was not merely decorative; it was a potent visual testament to their cultural fusion and their embracing, inclusive spirit. The specific colors and the manner of dress served as a non-verbal declaration of their membership and a constant, visible reminder of the diverse tapestry of individuals who proudly comprised the Guaiamuns.

The impact of the Guaiamuns extended far beyond the confines of their immediate territory. Their story is a powerful narrative of adaptability, resilience, and unity, leaving an indelible mark on the region’s cultural landscape. They embodied a community successfully navigating the profound societal transformations and pressures of 19th-century progress.

The conflicts between the various maltas were not random acts of violence but often highly ritualized, especially when they occurred on feast days. These holidays became traditional arenas for turf battles, usually triggered when one malta deliberately invaded the territory of another.

These confrontations on feast days were, therefore, more than just physical fights; they were symbolic rituals that vigorously reinforced the collective ethos and bonds of the maltas. They defined the groups’ collective identity and established their place within the broader, often indifferent, societal context of Rio de Janeiro.

—–A Lasting Legacy

the form of Capoeira practiced at this time in Rio de Janeiro is known today as CAPOEIRA CARIOCA.

Capoeira carioca, which flourished dramatically in the teeming urban landscape of 19th-century Rio de Janeiro, stood as a distinct and markedly more aggressive strain of the Afro-Brazilian art form. Crucially, it was fundamentally different from the modern, ritualized, and highly athletic iterations practiced globally today. Emerging from the city’s maltas (street gangs) and reflecting the harsh, often brutal realities of the era’s rapidly growing, volatile urban environment, Capoeira carioca was notorious for its raw violence, practical effectiveness, and focus purely on combat. This version of capoeira often explicitly eschewed the musical, acrobatic, and ritualistic elements that would later become central to the art in Bahia and its subsequent global spread, focusing instead on immediate combat efficacy and winning street confrontations by any means necessary. It was, first and foremost, a street-fighting discipline (capoeiragem) with deadly intent.

Key Characteristics and Techniques of Capoeira Carioca:

The fighting style of Rio’s capoeiras was dictated by the necessities of survival and dominance in an environment where law enforcement was often corrupt and violence was endemic.

- Focus on Utility and Combat: Unlike the widely practiced capoeira baiana from Salvador, Bahia, which integrated more dance, play, and ritual (the roda), capoeiragem carioca was a “no-nonsense” fighting system. The primary goal was self-defense and offense in chaotic and often life-threatening street confrontations. The movements were functional, direct, and aimed at incapacitating an opponent swiftly.

- The Aggressive Fighting Repertoire: Its fighting centered on five core categories of methods, many of which incorporated weapons:

- Foot Kicks and Sweeps (Rasteiras and other low sweeps): Used extensively to unbalance, trip, and quickly incapacitate opponents by targeting the legs and feet. While high, acrobatic kicks were rare, low, utilitarian sweeps were a signature move.

- Headbutts (Cabeçadas): A signature, close-quarters, brutal technique for delivering concussive force, often used to surprise a standing opponent or to break a grapple. It was a testament to the raw, visceral nature of the fighting style.

- Open Hand Blows and Strikes (Tapas or Pauladas): Included slaps, punches, and powerful strikes, frequently aimed at vulnerable targets like the face, ears (to disorient), and throat. The term pauladas suggests a heavy, club-like impact, even when using an open hand.

- Integration of Knives (Facas, Navalhas): The integration of blades was a critical, and often lethal, aspect of capoeira carioca. Fighters were known to carry and skillfully employ various knives, most infamously the navalha (razor), for swift and deadly effect, turning a fistfight into a life-or-death duel.

- Stick Fighting and Machetes (Cacetes, Facões): When a fight escalated beyond unarmed combat, the use of weapons was standard. Cacetes (cudgels or short sticks) and facões (machetes) were incorporated, demonstrating that the Carioca style was a holistic martial system that did not restrict itself to unarmed techniques.

- Rhythmic Variation: The Peneiração: The signature low, circling, shuffling step known as the peneiração (sifting or sifting movement) was heavily favored over the fluid, widely recognizable, and rhythmic ginga common in modern and Bahian styles. The peneiração allowed the fighter to maintain a low center of gravity, keep their knees bent for explosive movement, and be constantly ready to launch a fast, low attack or evade a blow, emphasizing preparedness over dance-like rhythm.

- Minimal Music and Ritual: Musical accompaniment was sparse, often limited to a single atabaque (a tall, wooden drum) or a similar drum to maintain a basic, driving rhythm, or sometimes no music at all. Music was a secondary element used to regulate the tempo of the fight, not the central ritualistic component it is in contemporary rodas. This lack of musical complexity further underscored the style’s focus on combat utility rather than cultural display.

The aggressive and often criminal reputation of the capoeiras cariocas ultimately led to their severe persecution and eventual near-extinction by the police and governing authorities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, solidifying their legacy as the most combative and ruthless historical expression of the art.

Ultimately, the saga of the 19th-century Maltas represents a crucial, often overlooked, chapter in the social and cultural history of Rio de Janeiro. They were a powerful dynamic convergence: an expression of marginalized culture finding power in unity, engaging in shrewd political maneuvering to survive, and embodying a unique Brazilian martial tradition rooted in honor and code. Their actions and their very existence left an indelible, complex legacy on the city, underscoring the deep currents of resistance, community, and political life that defined 19th-century urban Brazil the broader societal context.

Also around this time, appeared the iconic figure known as the MALANDRO.

In order to better understand who the malandro is, the term “malandro” derives from the word MALANDRAGEM, which encapsulates a range of meanings and cultural connotations. A malandro, often portrayed in Brazilian folklore, embodies characteristics of a clever rogue or a street-smart trickster who navigates life’s challenges with charm and cunning. This figure not only represents resilience but also reflects a deeper social commentary on the struggles and the adaptability of individuals within urban environments. As we explore the essence of the malandro, we uncover an intricate tapestry of cultural identity, revealing how this archetype serves as both a survival mechanism and a symbol of resistance in the face of adversity.

Malandragem is deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of Brazil and has been celebrated in various art forms, especially in the captivating rhythms of samba. This lifestyle of idleness, fast living, and petty crime is often depicted in the poignant lyrics of revered artists like Noel Rosa and Bezerra da Silva. The term encompasses a collection of strategies employed to gain an advantage in a given situation, often straying into the realm of illegality. It is characterized by savoir faire and subtlety, demanding a unique blend of aptitude, charisma, and cunning. The art of malandragem calls for a set of knacks and traits that enable the adept manipulation of individuals or institutions to achieve the most favorable outcome in the simplest manner possible. This cultural phenomenon sheds light on the complexities of human behavior and the societal structures that shape and are shaped by such behaviors.

The figure of the malandro in Brazilian culture is far more than a simple archetype; he is a complex social phenomenon, a living testament to resilience and street-smarts. Often celebrated and sometimes feared, the malandro embodies the characteristics of a clever rogue, a street-smart trickster who navigates the often-harsh realities of urban life with an undeniable blend of charm (jeitinho) and cunning. This enigmatic figure not only represents the individual’s capacity for survival but also serves as a potent reflection of deeper social commentary on the systemic struggles, inequalities, and the necessary adaptability of marginalized individuals within Brazil’s bustling, yet unforgiving, urban environments, particularly in cities like Rio de Janeiro.

Exploring the essence of the malandro reveals an intricate tapestry of Brazilian cultural identity. He is a master of situational ethics, demonstrating how resourcefulness can function as both a survival mechanism and a subtle, yet powerful, symbol of resistance against institutional adversity. The malandro exists outside the strictures of conventional labor and societal norms, instead choosing to live by his wits, often in a gray area between legality and crime.

In his complex role within society, the malandro was historically recognized for several key attributes:

- Capoeirista: The malandro was often a skilled practitioner of Capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian martial art disguised as a dance. This provided him with not only a formidable fighting skill but also a cultural identity and a community, embodying a tradition born of resistance among enslaved Africans. His movements were fluid, deceptive, and explosive, mirroring his approach to life.

- Cunning Criminal: While not always inherently violent, the malandro was certainly a master of deception and minor criminal enterprises. His criminality was often characterized by finesse—con artistry, gambling, and other petty crimes—rather than brute force. He was a smooth and charismatic operator, capable of charming his way out of difficult situations and managing to win the respect, and sometimes even the perverse affection, of his “victims” or rivals as he expertly maneuvered through the intricate and dangerous Brazilian underworld. His persuasive demeanor allowed him to exploit the weaknesses of others while maintaining an air of jovial innocence.

- Navalha as an Icon: The use of the NAVALHA, or straight razor, became an iconic and essential part of the malandro’s mystique. This razor, often concealed within his signature attire—a white suit, a Panama hat tilted just so, and brightly polished shoes—symbolized the unexpected and lethal nature of his actions. It was a weapon of last resort and a psychological tool, its presence adding significantly to the enigmatic and dangerous image of the malandro. The quick, precise flash of the razor underscored the inherent danger beneath his charming exterior, contributing to the potent mystique surrounding this intriguing figure.

The malandro’s narratives, woven into Brazilian folklore, have significantly enriched the nation’s cultural landscape. These captivating tales and legends illustrate the intricate interplay between popular culture, social history, and societal dynamics in Brazil. The archetype is not static; he has evolved from the rough-and-tumble street fighter of the early 20th century to the more stylized figure celebrated in samba music and cinema, yet his core message—that ingenuity can overcome institutional power—remains a foundational element of Brazilian identity.

This period in Brazilian history marked a significant shift in the social dynamics of the country. The abolition of slavery in 1888 brought about a time of immense change and challenge for the formerly enslaved individuals. As they sought to integrate into the new society, they faced numerous obstacles, including the struggle to find employment and establish their place alongside former slave-owners and other freed individuals.

Despite their efforts, prevalent prejudice and social discrimination persisted, relegating many former slaves to menial jobs and perpetuating their status as second-class citizens. The widespread prejudice prevailing at the time resulted in economic hardship for the majority of freed individuals, leaving them in impoverished conditions.

Additionally, the perception of Capoeira, a traditional Brazilian martial art form, was negatively impacted during this period. As the association between Capoeira and criminal elements grew, individuals skilled in Capoeira became intertwined with gangs, crime, and lawlessness. This unfortunate conflation further stigmatized Capoeira and solidified its association with criminality in the public eye, perpetuating an ongoing cycle of societal bias and misunderstanding.

The ramifications of this historical period reverberated for decades, influencing the trajectory of Capoeira and the social standing of formerly enslaved individuals in Brazilian society.

In 1890, following the Proclamation of the Republic of Brazil in 1889, the decree 847 of 1890, titled “Of the vadios and capoeiras,” was enacted. This decree sternly condemned capoeira and its practitioners, going so far as to make the practice of capoeira illegal. However, in reality, this decree served as a form of public relations, creating the appearance of taking action against the escalating crime rate in Brazil. It’s important to note that this was actually a double standard, as many bodyguards were being hired precisely for their expertise in capoeira, highlighting the inconsistency in the government’s approach to the martial art. The historical context surrounding the criminalization of capoeira provides insight into the complex social and political dynamics of the time, shedding light on the nuanced relationship between the Brazilian authorities and the practice of capoeira.

The history of Capoeira is deeply intertwined with resistance and subversion. During the colonial period in Brazil, Capoeira was outlawed, and practitioners faced severe consequences for their involvement in this art form. Punishments could be brutal, and Capoeiristas often had to resort to using aliases and nicknames in order to protect their identities and continue practicing. This tradition of using nicknames, or “apelidos,” has persisted through the years, serving as a reminder of the clandestine origins of Capoeira and the resilience of its practitioners.

Also, there was the berimbau rhythm known as CAVALARIA, that warned of the approach of police patrols.

To enforce these laws, the president hired a man named Sampaio, who was reputed to be the most ruthless police chief in Brazil’s history. He was determined to extinguish Capoeira. What is interesting about Sampaio was that he himself was an excellent Capoeirista. He was a terror to the gangs and was said to have faced many legendary fighters of the time, even some who were rumored to have corpo fechado (a condition magically rendering the fighter impervious to bodily injury). Sampaio’s special police force also learned Capoeira, so they were able to challenge their “enemy” on their own ground.

Sampaio’s dual role as a ruthless enforcer of the law and an adept Capoeirista added an intriguing layer to his character. His proficiency in Capoeira not only contributed to his fearsome reputation but also enabled him to engage with the Capoeira community on a unique level. The fact that he was willing to confront rumored holders of corpo fechado speaks volumes about his courage and his unwavering commitment to his mission. His approach, training his police force in Capoeira as a means of combating the practice, reflects a cunning strategy that aimed to dismantle the culture from within. This historical context provides a fascinating insight into the complexities of power dynamics and cultural resistance in Brazil during that era.

Had it not been for the strong resistance by the Capoeiristas, as well as support by influential people, he may have succeeded in his mission. However, one incident brought Sampaio’s relentless pursuit of Capoeiristas to an end. He arrested a man named Juca Reis, a member of the gentry, for practicing Capoeira and demanded that he be expatriated. This caused a crisis for the government. The members of the president’s cabinet opposed this action because Juca’s father was well known and favored by many politicians.The president called a special meeting of his cabinet, and after eighteen days, two important members of the cabinet resigned and Juca was expatriated.

Over time, under intense legal persecution, the heads of the maltas were gradually incarcerated, exiled, or exterminated, and they were losing their strength and being dismantled. And the practice of capoeira receded until it was alive and well in only a few cities: Recife, Rio de Janeiro, and Bahia. Also in this time, there were a few legendary characters that appeared, known for their skill in capoeira. This period marked a significant decline in the influence of the maltas, as the forces against them intensified their efforts, leading to a dispersal of the once powerful groups. Despite the challenges, capoeira managed to survive and thrive in select urban centers, where devoted practitioners kept its flame burning. The legendary characters that emerged during this tumultuous era became symbols of resilience and determination, embodying the spirit of capoeira as they navigated through adversity with their exceptional skill and expertise. Their presence served as a source of inspiration for the remaining practitioners, rejuvenating the art form and keeping its heritage alive in the face of formidable odds. The perseverance of capoeira in the face of such trials stands as a testament to its cultural significance and enduring appeal, reflecting the resilience and indomitable spirit of its practitioners.

The story of Nascimento Grande, the intensely feared Capoeirista from Recife, the Capital of Pernambuco, is shrouded in mystery and legend. Leading his band through the vibrant Carnaval each year, he became a prominent figure in the local folklore and history of the early 1900s. However, his fate remains uncertain, as conflicting accounts of his disappearance persist to this day. Some believe that he met his demise in a dramatic police raid, while others speculate that he chose to start afresh in Rio de Janeiro, assuming a new identity to live out the rest of his days.

Nascimento Grande’s presence and enigmatic legacy have left an indelible mark on the cultural tapestry of Recife, captivating the imagination of generations and fueling countless tales of his exploits. His impact on the world of Capoeira and the aura of mystery surrounding his final chapter continue to intrigue historians, enthusiasts, and storytellers alike, ensuring that his name remains etched in the annals of Brazilian folklore.

In the Brazilian capital (At the time) Rio de Janeiro, While the government largely extinguished the practice there, its essence was preserved by a few dedicated masters. Notably, Mestre Sinhozinho (Antônio Ricardo de Oliveira, 1891–1962) kept the utilitarian spirit alive. He taught a highly pared-down “combat capoeira” (often called “Luta Regional”) that stripped away virtually all musical, ritualistic, and dance components, focusing purely on self-defense and fighting techniques, thus serving as a vital, if hidden, link to the aggressive carioca tradition. It was this focus on utility that later informed the development of other practical, regional styles.

Also, there was MANDUCA DA PRAIA, an older Capoeira, always dressed in the utmost elegance and had, it was said, twenty-seven criminal charges against him – all dropped because of the influence of the politicians who secretly employed him. Manduca’s enigmatic persona combined with his formidable skills in Capoeira made him a figure of intrigue and fear in the streets of Rio de Janeiro, leaving behind a legacy that continues to fascinate. His ability to maneuver through the political landscape and evade legal consequences not only reinforced his aura of mystery but also spoke to the complex power dynamics at play during that era.

And later, we have MADAME SATA, a central figure in the cultural and social fabric of Rio de Janeiro. Madame Sata, a drag queen and a legendary fighter, defied societal norms and overcame immense hardship to become a symbol of resilience and individuality. With a history marked by incarceration and perseverance, Madame Sata’s story reflects the tumultuous yet vibrant spirit of Rio’s underground scene. His endurance in the face of adversity and his impact on the local community solidify his place in history as an emblem of strength and defiance.

These individuals, Manduca da Praia and Madame Sata, represent the rich tapestry of Rio de Janeiro’s history, embodying the complexities and contradictions of a city marked by both glamour and grit, elegance and struggle, and a determination to carve out identity in the face of adversity.

And in Bahia (And the RECONCAVO, the interior), There were left a few legendary Capoeiras like BESOURO MANGANGA. I’ll tell you more about him on another PAGE. There were many others of course, who all contributed to what I like to call “The age of the valentaos (Tough Guys)”.

In Bahia, the spirit of capoeira lives on through the stories and legends of fighters like Besouro Mangangá, whose skill and bravery continue to inspire new generations of capoeiristas. The vibrancy of the Reconcavo and the interior of Bahia has nurtured a rich tradition of capoeira, where the fusion of martial arts, dance, and acrobatics reflects the diverse cultural tapestry of the region.

The legacy of Besouro Mangangá and other legendary capoeiristas is deeply woven into the fabric of Bahia’s history, embodying the resilience and spirit of the Brazilian people. Their contributions during “The age of the valentaos” remain a testament to the enduring power of capoeira as both a martial art and a symbol of resistance.

To delve deeper into the captivating story of Besouro Mangangá and explore the philosophical underpinnings of capoeira, visit the dedicated page on our website and embark on a journey through this captivating world of philosophical explorations and cultural heritage.

By the 1920’s, the law that prohibited the practice of Capoeira was still in effect, and its practice was still disguised as a “folk dance”. In their hidden places, Capoeiristas did their best to keep the tradition alive, and by presenting it as a folk art, they made the practice of Capoeira more acceptable to society, although it continued to have an unsavory reputation with mainstream Brazilian society, which kept it illegal.

Despite the challenges and the legal restrictions, a pivotal figure emerged to change the destiny of capoeira forever. This influential figure was none other than Manoel Dos Reis Machado, remembered and revered as MESTRE BIMBA. Mestre Bimba’s profound impact on the art form cannot be overstated. He dedicated his life to preserving and promoting capoeira, elevating it from a clandestine and marginalized practice to a celebrated and respected martial art and cultural expression.

Mestre Bimba’s impact on the world of capoeira extended far beyond his own practice. In 1932, he opened the first capoeira academy in the city of Salvador, an unprecedented move at the time. This marked a crucial moment in the history of capoeira, as it had previously been practiced only on the streets and in private locations. Through the establishment of his academy, Mestre Bimba sought to promote capoeira as a legitimate art form and to secure its future by elevating its status within Brazilian society. His efforts were met with significant success, and his academy thrived, drawing attention not only from within Brazil but also from international visitors.

Mestre Bimba’s commitment to preserving the traditions of capoeira while also innovating within the art form was highly influential. He developed a new style of capoeira, known as “capoeira regional,” which incorporated systematic training methods and introduced sequences of movements that differed from the more spontaneous style of traditional capoeira. This emphasis on formalizing the teaching of capoeira and structuring its practice played a pivotal role in establishing it as a respected martial art.

Furthermore, Mestre Bimba dedicated himself to challenging stereotypes and misconceptions about capoeira. He actively sought to dispel the prejudices that had long surrounded the art form, particularly those related to its association with Afro-Brazilian culture. Through his teachings and demonstrations, he worked to redefine the public perception of capoeira, highlighting its deep cultural significance and its value as a vehicle for self-expression and community cohesion.

Previously, it was said that every capoeirista had his own style but Mestre Bimba brought in a training system that consolidated the techniques and refined the art. He also recognized that like other world martial arts, capoeira needed a code of ethics before its reputation could be restored and it could get accepted by people outside the criminal underworld as a part of Brazilian heritage. The honor code developed for Regional capoeira included rules such as:

- No smoking or drinking alcohol.

- Skills should only be demonstrated inside the roda, allowing for the element of surprise should a real fight situation occur. (The roda is a circle formed by people, inside which, practice fights take place)

- When training, the capoeira fighter should focus on the task at hand.

- Talking in the roda should be kept to a minimum

- Other ‘players’ should be watched in a bid to learn more. (In capoeira the term ‘player’ is deemed correct, unlike in many other martial arts).

- The ginga (the fundamental move in capoeira shown being taught by Bimba below) and other basic capoeira moves should be practised as often as possible.

- Do not be afraid to get close to your fighting opponent as the more you do this, the more you will learn.

- The capoeira fighter’s body should be kept relaxed.

- It is better to be defeated in the roda than in a real fight situation.

These principles not only helped to elevate capoeira from its associations with criminal activities but also fostered a sense of camaraderie and mutual respect among practitioners. The establishment of such ethical guidelines played a crucial role in transforming capoeira into a celebrated and respected cultural expression, garnering recognition as a valuable part of Brazil’s rich heritage.

Notably, Mestre Bimba was known for excelling in the martial aspect of capoeira, earning a fearsome reputation as a skilled fighter. His prowess extended beyond the capoeira community, as he won challenge matches against practitioners of other martial arts such as boxing and jujutsu. This elevated his status and brought him fame as a remarkable and respected fighter.

Mestre Bimba’s legacy endures through the enduring impact of Capoeira Regional, influencing countless practitioners and enthusiasts worldwide while preserving the rich cultural heritage of this captivating martial art form.

Capoeira Regional was created in reaction to the street Capoeira of the twenties.

The legacy of Mestre Bimba’s revolutionary approach to capoeira continues to resonate within the martial arts community. His recognition of the need to adapt traditional teaching methods to cater to the diverse backgrounds of his students paved the way for a transformation in the way capoeira was both taught and perceived. By introducing a systematic and structured approach to instruction, Bimba not only improved the technical quality of movements but also underscored capoeira’s significance as a form of self-defense and athleticism.

Notably, Bimba’s emphasis on training sequences, exemplified in the swift and aggressive nature of his methodologies, distinguished his style from the traditional Capoeira Angola. His incorporation of techniques such as the Cintura Desprezada and unique arm-locks added a dynamic and distinctive dimension to his teachings, captivating the attention and intrigue of practitioners and observers alike.

Mestre Bimba also created the time honored tradition of the Batizado. A batizado (literally “baptism” in Portuguese, and borrowed from the religious tradition) is normally an annual event for a capoeira group in a region or country.

The tradition of the batizado holds a special significance within the capoeira community. It marks the pivotal moment when a new student participates in their first game of capoeira to the compelling rhythm of the berimbau, a defining instrument in this art form. During the batizado, the new student engages in a game with a more experienced practitioner who acts as a guide, supporting the beginner as they cultivate their capoeira skills. This ceremonial event serves as a warm welcome for new members into the school, fostering a sense of belonging and camaraderie among practitioners.

In contemporary capoeira circles, batizados have evolved into grand gatherings that carry significant importance for the organizing group. It signifies the juncture in the calendar when new members are formally initiated into the group, marking the bestowal of their inaugural cords. Additionally, existing members, based on their progression, may also receive a new cord. A typical batizado spans several days and encompasses various components, including workshops, the batizado itself, and a troca de cordas (cord exchange ceremony). It is common for multiple groups from diverse regions to converge at a batizado, facilitating the exchange of techniques, insights, and styles, thus contributing to the continued evolution and enrichment of the capoeira game.

Here’s an example of a modern Batizado:

Normally, the mestre of the group must be present during the proceedings, but historically this was not required.

“Mestre Bimba, a legendary figure in the world of capoeira, not only showcased his incredible musical talents in his album, but also introduced the songs and rhythms that were integral to his unique methodology. The album, a true reflection of the soul of capoeira, can be enjoyed on the dedicated page Here. Interestingly, Bimba emphasized the Brazilian roots of capoeira, likely influenced by the predominantly white patrons of his time. Despite this emphasis, it was the pedagogical method developed by Bimba that truly revolutionized the art, making it accessible even to the affluent white demographic.

Following this period, Bimba’s students, including some who were sons of influential politicians, embarked on a mission to legalize capoeira. This effort gained momentum during the 1930s, a time when Brazil was under the dictatorship of Getulio Vargas. Vargas, despite being a fascist, recognized capoeira as a national art that deserved promotion rather than prohibition. As a result, new laws were established, permitting the teaching of capoeira in licensed academies and enabling public demonstrations with the necessary permits.

Under the guidance of Mestre Bimba, capoeira experienced a profound evolution, drawing inspiration from its rich historical roots while transcending boundaries and redefining the art form for generations to come. Bimba’s visionary approach and unwavering commitment to innovation have left an indelible mark on capoeira, ensuring its enduring relevance and influence in the realm of martial arts.”

And While Regional grew like crazy during the 1950s thru the 1970s, what became of the old style, Capoeira Angola?

Well, Capoeira Angola survived (Obviously, since I created a website about it), thanks mostly to the efforts of Bahia’s most famous master, Vicente Ferreira Pastinha , or Mestre Pastinha, He lived from 1889 to 1981.

Vicente Ferreira Pastinha, a true legend in the world of Capoeira, had an intriguing and eclectic background that greatly influenced his contributions to this martial art form. Born to José Pastinha, a hardworking Spanish immigrant, and Eugênia Maria de Carvalho Ferreira, a dedicated black Bahian homemaker, Pastinha’s upbringing shaped his passion and dedication to Capoeira. It was at the tender age of 8 that the young Pastinha was introduced to Capoeira by an African man named Benedito, setting the stage for his lifelong devotion to this art.

During the period from 1902 to 1909, Pastinha shared his knowledge and expertise in capoeira with his peers at the School of Sailor Apprentices. However, in 1912, he halted his teaching activities and distanced himself from capoeira for close to three decades. It wasn’t until 1941, when he was urged by other mestres of his time, particularly Amorizinho, that Pastinha established the first Angola school, the Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola, situated in the vibrant Pelourinho. This marked a pivotal moment in the history of Capoeira, as Pastinha’s school became a cornerstone for the preservation of this art form.

One notable aspect of his school was the distinctive dress code adopted by his students, who would commonly be seen in black pants and yellow T-shirts, mirroring the colors of his beloved soccer club, Esporte Clube Ypiranga. Pastinha’s teaching style was traditional, devoid of a formal method, relying on observation and oral instruction to perpetuate the rich heritage and customs of Capoeira.

To delve deeper into the fascinating legacy of Vicente Ferreira Pastinha and his indelible mark on Capoeira, feel free to explore further by clicking HERE.

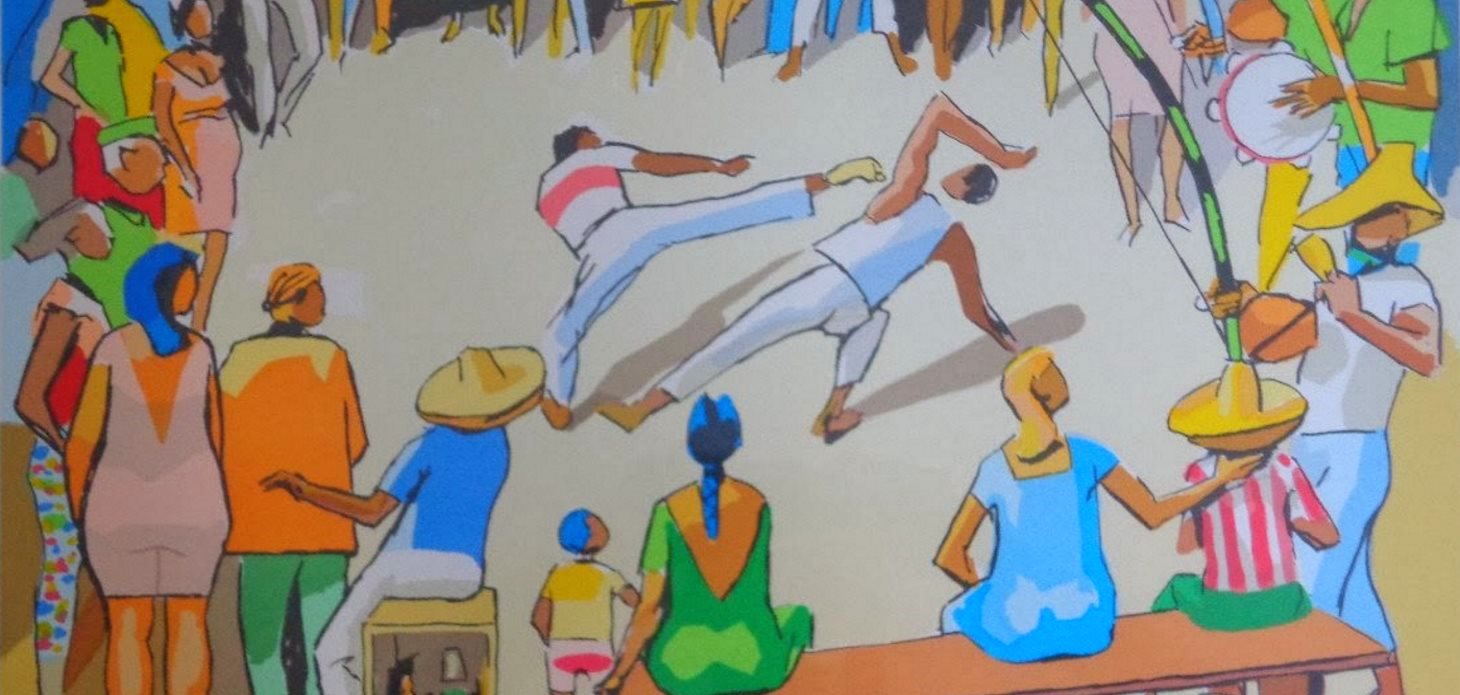

The spread of capoeira as a cultural phenomenon has been truly remarkable. Originating as a martial art in Brazil, it has now evolved into a global ambassador of Brazilian culture. Since the 1970s, capoeira masters have ventured beyond Brazilian borders to impart their knowledge in various countries. This has led to the establishment of capoeira communities on every continent, drawing in numerous international students and tourists to Brazil each year. These enthusiasts often make dedicated efforts to learn Portuguese, seeking a deeper understanding and integration into the essence of this art form. Furthermore, esteemed capoeira masters, whose reputations precede them, frequently travel abroad to impart their expertise and even set up their own training establishments. The captivating and visually stunning nature of capoeira performances, characterized by theatrical flair, acrobatics, and a diminished focus on combat, has become a common spectacle across the globe.

And now, I have something special for you.

What I have posted on these last 2 pages are MY OPINION on the history of this artform.

An informed opinion perhaps, but still, my opinion.

However, I feel it’s my responsibility to share with all of you as much factual information regarding all aspects of Capoeira Angola, so you can check it out for yourselves. My research into Capoeira angola is ONGOING, and if you’re serious about this way of life, then you should never stop learning about this art. The new Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History has published A summary of the history of capoeira and an overview of the existing literature and primary sources. All free, and totally accessible.

It’s important to understand that Capoeira Angola is not just a martial art but a cultural expression deeply rooted in the history of Brazil. Its origins can be traced back to the period of slavery in Brazil, and it has evolved over the centuries into a multifaceted art form that encompasses music, dance, acrobatics, and a unique sense of community.

As you delve into the rich history and practice of Capoeira Angola, you will come across a wealth of stories, traditions, and perspectives that contribute to its tapestry. The ongoing research into this artform allows us to gain deeper insights into its historical significance and its enduring relevance in contemporary society.

Exploring the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History provides an invaluable resource for anyone seeking to expand their understanding of Capoeira Angola. By accessing the summary of its history and engaging with the existing literature and primary sources, you can enrich your knowledge and appreciation of this captivating artform. Embracing the spirit of continuous learning and discovery is fundamental for anyone dedicated to the study of Capoeira Angola.

Through ongoing research and an open-minded approach, we can honor the legacy of Capoeira Angola and contribute to its preservation and evolution. The accessibility of resources such as the Oxford Research Encyclopedia empowers individuals to immerse themselves in the multifaceted world of Capoeira Angola, fostering a deeper connection to its cultural significance and historical roots.

Click HERE to check it out.

And, click HERE to gain free access to the book, “Capoeira – The history of Afro Brazilian Martial Art” by Matthais Rohrig Assuncao, which you can get on amazon by clicking HERE.

And, click HERE to gain free access to one of my all-time favorite capoeira books, “Ring of liberation : deceptive discourse in Brazilian capoeira”, by J. Lowell Lewis. You can also get it on amazon by clicking HERE.

And last, but certainly not least, I want you all to watch this video:

Dance of the Disorderly: Capoeira, Gang Warfare, and How History Gets in the Brain

Talk by Dr. Greg Downey + post-talk live capoeira demo

Tuesday, December 2, 2014

St. Mary’s Hall, Multipurpose Room

University of Maryland, College Park

Presented by the Latin American Studies Center

with departments of Anthropology and Physical Cultural Studies/Kinesiology

The Afro-Brazilian dance and martial art, capoeira, was once associated with urban gangs called capoeiras and desordeiros or “disorderlies.” They were individuals – mostly men – who thrived on the margins of Brazilian urban society. Alternately turned to as political enforcers and turned upon and persecuted as a target of moral panic, the gangs left contemporary Brazil both a rich performance tradition and a complex record of their way of life. Downey explores accounts of mayhem, trickery, and violence. Even though capoeira is now legal and openly practiced, even endorsed by the state, many practitioners seek to maintain the sense that they are practicing “disorder.” Downy presents a phenomenology of heroic self constitution, especially drawing on song texts and autobiographies from venerated masters. He examines a distinctive way of inhabiting an urban environment and of capoeira practitioners whose careers in the art straddled the divide between quasi-illegality and growing respectability

Greg Downey is Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Anthropology at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia). Interested in neuroanthropology, or the relation between human cultural diversity and neurological variation, Dr. Downey has done field research on sport in Brazil, Australia and the United States. He is author of Learning Capoeira: Lessons in Cunning from an Afro-Brazilian Art, and co-founder and regular writer for Neuroanthropology, a weblog at the Public Library of Science (PLOS).

Category

Education

License

Standard YouTube License

I was just going to just post the above video and have everyone watch it, because in that video, among other things, Greg Downey talks about Brazil’s 19th century history and Capoeira’s role in it far better than I can on one web page. But, I figured, the video wasn’t gonna last forever…

Capoeira Angola holds a significant place in the history and culture of Brazil. Originating as an ancient martial art with African roots, it became a potent tool for resistance against the oppression of enslavement. The very practice of Capoeira was once deemed illegal, and those found engaging in it risked facing the ultimate penalty: death. This resulted in nearly four centuries of clandestine teaching and practice, shrouded in secrecy as the art form persisted through the hardships of slavery.

It was not until the 1930s that Capoeira Angola finally emerged from the shadows, with its prohibition lifted and the recognition of its cultural and martial significance. The resilience of those who safeguarded and transmitted Capoeira Angola throughout this tumultuous history is a testament to their unwavering dedication and determination. Practitioners of Capoeira Angola today carry this legacy forward, bearing the responsibility of honoring and preserving this rich heritage that endured against all odds.

To learn, practice, preserve, and show this beautiful way of life called Capoeira Angola to the world. And, to pass it on to the next generation, and beyond…

The practice of Capoeira Angola extends far beyond the realm of physical movement; it encapsulates the essence of Brazilian culture and history. The rhythmic resonance of the berimbau sets the tone for the fluid, acrobatic motions that characterize this art form. From the captivating ginga to the mesmerizing sequences of attacks and defenses, every aspect of Capoeira Angola reflects the rich and diverse heritage of Brazil. It serves as a conduit for individuals to not only engage with their roots but also to create a legacy for future generations. The sense of camaraderie and community fostered through Capoeira Angola is unparalleled, weaving together individuals from different walks of life into a vibrant, interconnected global network. By embracing Capoeira Angola, one becomes an ambassador of tradition, unity, and cultural preservation, ensuring that the spirit of this art form continues to thrive for years to come.