This blog series, titled “SPIRITUAL PRACTICES OF AFRICA, AND THE DIASPORA,” is dedicated to a thorough exploration of the diverse indigenous beliefs and established religions across Sub-Saharan Africa. The central themes of this investigation revolve around the foundational spiritual practice of ancestral worship, alongside the major global faiths of Christianity and Islam, which have profoundly shaped the region’s spiritual landscape.

A key focus of the series is to illuminate the richness of the region’s cultural heritage, which is vibrantly expressed through various rituals and community gatherings. These practices are not merely historical relics; they are living traditions that actively reinforce collective identity, provide social cohesion, and serve as crucial mechanisms for cultural transmission from one generation to the next.

Furthermore, the series critically examines the dynamic adaptation and evolution of these traditions as they take root and flourish within the African diaspora. A particular emphasis is placed on the power of storytelling—an invaluable method for preserving the voluminous oral histories of the continent and effectively passing down essential life lessons, moral codes, and cultural wisdom to future generations across the globe. Ultimately, the comprehensive goal of this series is to foster a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between faith, identity, and the extraordinary cultural resilience demonstrated by the peoples of this region and its diaspora.

—–Exploring the Core: Defining African Traditional Spirituality

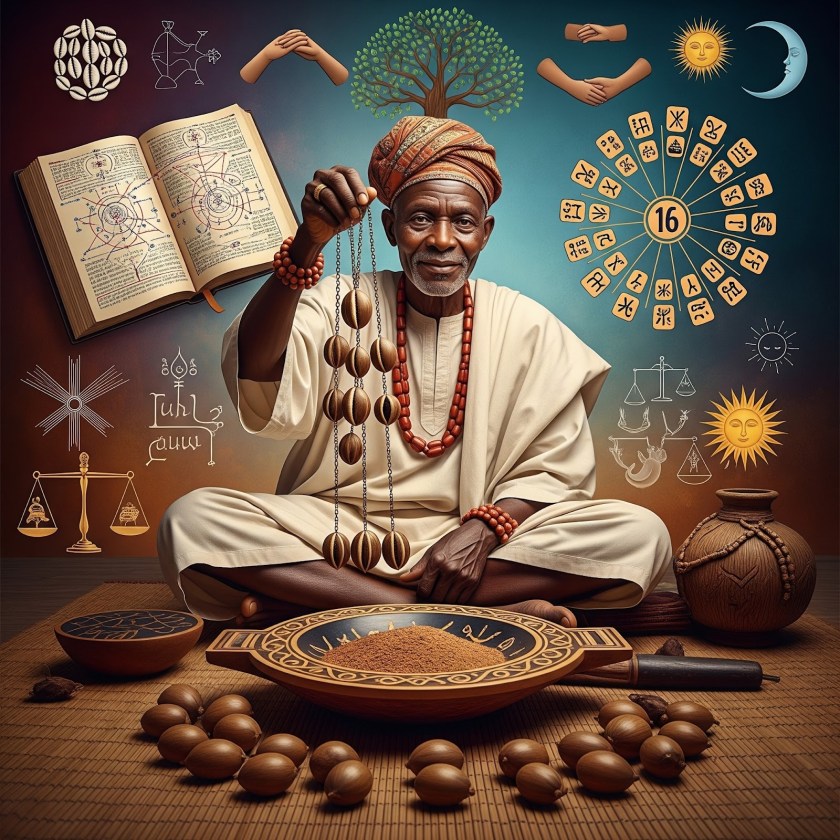

In today’s installment, we pivot to address a fundamental and enduring set of questions: Exactly what constitutes traditional African Spirituality? Intriguingly, since the inception of this blog series, this core spiritual foundation has been referenced but never fully and directly explored. This post is intended to rectify that oversight, serving as a critical entry point into the specific beliefs and practices that predate, or exist parallel to, the Abrahamic faiths in Africa.

This deep dive into African Traditional Religion (ATR) was specifically inspired by the journey of a man named Arasa Malik, a compelling figure whose personal quest to uncover and reconnect with the authentic spiritual foundation of his ancestors mirrors the quest of countless individuals both on the continent and in the diaspora. His experience provides a powerful, relatable anchor for this exploration.

Navigating the Landscape of African Spirituality: Key Questions

To properly frame this complex and multifaceted topic, this post will seek to answer several critical questions often posed by those new to the subject or seeking deeper engagement, providing both clear definitions and nuanced distinctions:

The Core Questions: What is African Traditional Religion (ATR)?

African Traditional Religion (ATR) is a complex and profoundly diverse spiritual and cosmological phenomenon that defies easy categorization. It is fundamentally crucial to establish a clear and nuanced working definition of ATR, primarily by recognizing what it is not: it is not a single, monolithic religion comparable to the structured, centralized organizations of global faiths. Instead, ATR represents a vast, interconnected collection of indigenous spiritual, ethical, and moral systems that were organically developed and practiced across the African continent long before the widespread arrival of the major Abrahamic religions, namely Christianity and Islam.

Core Commonalities Amidst Vast Diversity

The immense geographical, ethnic, and linguistic scope of Africa results in a rich tapestry of distinct ATR expressions. Practices, specific deities, and rituals vary drastically—from the intricate pantheon of Orishas (as found among the Yoruba people of West Africa) and the Abosom (among the Akan) to the worship of Nyam (among the Tiv) and the traditional beliefs of the Zulu in Southern Africa.

However, beneath this vast regional variation lies a set of fundamental, universally shared commonalities that allow us to define ATR as a cohesive, though decentralized, religious category:

- Belief in a Supreme Being: Nearly all ATR systems acknowledge the existence of a singular, all-powerful Creator God. This Supreme Being (known by countless names, such as Olodumare in Yoruba or Unkulunkulu in Zulu) is often perceived as a distant or transcendent figure, a primal force whose will governs the universe but who is rarely directly petitioned.

- Reverence for Ancestors (Ancestral Veneration): Perhaps the most distinctive and crucial element, ATR holds that the deceased—especially righteous and impactful family members—do not simply vanish but transition into a powerful spiritual state. These Ancestors (living-dead) act as intermediaries between the living community and the Supreme Being or the other divinities, offering guidance, protection, and moral oversight. Maintaining a positive relationship with the Ancestors through rituals and respect is essential for the community’s well-being.

- Holistic Cosmology and Interacting Worlds: ATR posits a universe where the spiritual world (inhabited by the Supreme Being, divinities, and Ancestors) and the physical world (the realm of humans, animals, and nature) are not separate but are constantly interacting and interdependent. Life is viewed holistically; spiritual health is inseparable from physical, communal, and environmental health.

- Community Harmony and Ethos: The focus of worship and ritual is often less on individual salvation (as in Abrahamic faiths) and more on maintaining and restoring communal balance, harmony, and peace (Iwa Pele in Yoruba). Religious practice is inherently social and communal, reinforcing ethical standards and the collective identity.

- Ritual for Maintaining Balance: Ritual is the vital mechanism used to bridge the spiritual and physical worlds. Through rites of passage (birth, puberty, marriage, death), seasonal festivals, sacrifices, and offerings, the community seeks to maintain or restore balance with nature, the spirit world, and the Ancestors. This practical spirituality ensures the fertility of the land, the health of the people, and the continuity of tradition.

Our definitive understanding of African Traditional Religion must, therefore, acknowledge this shared foundational structure of belief and practice while simultaneously respecting and highlighting the immense regional, ethnic, and linguistic diversity that renders each specific ATR expression a uniquely rich and distinct spiritual system.

How do I know what African Traditional Religion is for me and how do I join?

This tackles the deeply personal journey aspect, demystifying the process of alignment, spiritual calling, and potential initiation into a specific ATR lineage. Unlike joining a conventional, centralized, and globally-uniform religion (like signing a membership card or simply attending a service), aligning with and joining an ATR is typically a lineage-based, community-driven process. It is rarely a matter of simple choice or ‘shopping around.’ The process usually involves:

- A Spiritual Calling/Diagnosis: Often, an individual’s need for initiation is revealed through divination (e.g., Ifá, Fa, etc.) by a recognized and reputable elder or priest/ess, who determines which specific path, Orisha, or ancestral work is required for that individual’s destiny (or ori).

- Lineage and Community: Joining means being initiated into a specific temple, house, or lineage that traces its authority back generations. There is no central ATR headquarters; the authority resides in the ocha (house) and the established priesthood.

- Initiation: The process involves rigorous, often lengthy, and sacred rituals of purification, learning, and commitment that formally connect the initiate to the deities, ancestors, and the community.

This section will emphasize that the journey is guided by spirit and tradition, not personal preference alone.

What is African Spirituality?

We will distinguish ‘African Spirituality’ from ‘African Traditional Religion.’ African Spirituality is examined as a broader, often more fluid philosophy and worldview that is not necessarily tied to the formalized ritual structure or initiated priesthood of a specific ATR. It is the underlying cultural ethos—the way a person of African descent views the cosmos, ethics, community, and the essential relationship with nature. African Spirituality influences all aspects of life and may manifest as:

- A generalized reverence for ancestors.

- A strong sense of communalism and interdependence (Ubuntu is a classic example).

- Belief in the life force that pervades all things (animism).

- The use of traditional healing, herbalism, and cultural practices for mental and physical well-being.

One can hold an ‘African Spiritual’ worldview without being formally initiated into a Traditional Religion.

What are African Traditional Religions (ATRs) and African DIASPORA Traditional Religions (ADTRs)?

A critical and nuanced comparison will be drawn between the practices as they exist on the continent (ATRs) versus their evolved, syncretic forms in the Caribbean, North America, and South America (ADTRs).

- African Traditional Religions (ATRs): Practices maintained within their native, often tribal, and linguistic environments in Africa. They have a continuous, unbroken lineage in their original cultural context.

- African Diaspora Traditional Religions (ADTRs): These are the systems that developed out of the forced migration and enslavement of African peoples. They retained the core cosmological principles of ATRs but evolved through syncretism—the blending of African practices with the dominant religions (primarily Catholicism) of the Americas to survive and hide in plain sight. Key examples include:

- Haitian Vodou: (from Fon/Yoruba/Kongo traditions)

- Santería/Lucumí: (from Yoruba traditions, Cuba)

- Candomblé: (from Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu traditions, Brazil)

- Palo Mayombe: (from Kongo traditions, Cuba)

This section will highlight the shared ancestral source and the crucial differences in structure, syncretism, and cultural context.

What are some of the key differences in practicing African Spirituality versus Traditional Religions?

This section will highlight the practical, philosophical, and commitment-based distinctions between holding a spiritual worldview and adhering to a formalized system.

| Feature | African Spirituality (Worldview) | African Traditional Religion (System) |

| Commitment | Fluid, personal, and philosophical. | Formal, initiated, and requires adherence to specific lineage rules. |

| Ritual | Often informal; personal prayers to ancestors, general cultural practices. | Highly formalized, prescribed rituals led by an initiated priesthood. |

| Priesthood | Not required; personal engagement. | Requires formal initiation and adherence to the authority of a priest/ess (e.g., Babalawo, Iyalorisha, Houngan). |

| Scope | A way of viewing the world and living ethically. | A complete religious system with specific cosmology, myths, and worship of defined deities/forces. |

A couple of common myths about joining ATRs:

We will debunk common misconceptions and stereotypes that often surround these practices, providing accurate, respectful context. Myths often include:

- Myth: “You can just read a book and become a practitioner.” Fact: Initiation and practice are almost always lineage-based and require a spiritual elder/community.

- Myth: “They are primitive and monolithic.” Fact: ATRs are highly complex, philosophical systems with sophisticated moral codes and specialized knowledge passed down through oral tradition.

- Myth: “All ATRs involve ‘black magic’ or devil worship.” Fact: This is a harmful, Eurocentric mischaracterization. The focus is on balance, healing, and destiny.

How do you know which one is the right one for you? (Guidance for Seekers)

This concluding section is dedicated to offering thoughtful and responsible guidance for those who feel a genuine call to connect with an Ancestral Tradition (ATR). It is crucial to understand that embarking on this path is not a casual or transactional “choose your own adventure.” Instead, it demands a careful, respectful, deliberate, and often humble approach, emphasizing spiritual alignment over intellectual preference.

- Personal Research and Spiritual Calling:

The journey begins not with commitment, but with respectful, comprehensive, and objective research. Start by diligently investigating your own ancestral background and lineage. Understanding the geography, history, and cultural context from which your ancestors came can sometimes illuminate a path. Beyond mere academic study, however, it is vital to remain open to the possibility of a direct spiritual calling. This is a profound, intuitive pull or repeated spiritual nudge that guides you toward a specific tradition, often transcending a purely intellectual choice or a decision based solely on convenience or curiosity. A genuine path will often choose you before you definitively choose it. This stage requires patience, introspection, and a readiness to listen more than to speak. - Divination: The Definitive Spiritual Consultation:

For nearly all established Ancestral Traditions, the definitive and required way to discern if a specific ATR—and, more specifically, a particular house or lineage within it—is “for you” is through traditional divination. This crucial process must be performed by a respected, verifiable, and legitimate initiated practitioner (such as an Ifá priest, Vodou Houngan/Mambo, or similar title). Divination is not fortune-telling; it is a sacred process believed to consult your ori (a concept encompassing the head, destiny, and personal spiritual guide) and the spirits, ancestors, and/or Orishas/Deities for definitive, personalized guidance. This consultation determines if your spiritual destiny aligns with the path, which gods/forces you are meant to serve, and what is required for your well-being. A path chosen without this spiritual validation is generally not considered legitimate or sustainable.

Finding Legitimate Practitioners and Communities:

The integrity of your spiritual journey hinges almost entirely on the legitimacy and ethical conduct of the person and community you engage with. Emphasis must be placed on finding reputable, formally initiated, and ethical practitioners and communities (often referred to as houses, temples, or ilé).

- Verifiable Lineage: A legitimate practitioner should be able to articulate and ideally verify their lineage—the chain of initiation that connects them back to the origins of the tradition. This ensures the integrity and purity of the knowledge and rites.

- Commitment to Ethics and Tradition: Look for communities that demonstrate a deep, unwavering commitment to the ethical principles of their tradition, community service, and maintaining traditional practices without substantial modern dilution or appropriation.

- The Red Flags: Be highly cautious and immediately avoid any individual or group that:

- Promises instant power, guaranteed wealth, or quick, transactional solutions.

- Charges exorbitant, non-traditional fees for basic consultation or initiation.

- Lacks a tangible, well-established community or house structure.

- Engages in practices that feel coercive, threatening, or are fundamentally disrespectful to the cultural origins of the tradition.

The genuine path to a fulfilling and meaningful existence is not marked by a swift and easy acquisition of worldly wealth or immediate personal fame. Instead, it is a demanding journey built upon the three essential pillars of dedicated service, rigorous self-improvement, and deep connection with others and the world around us.

Dedicated Service forms the foundation, demanding an outward focus where one’s skills, time, and energy are consistently channeled toward the betterment of the community and the alleviation of suffering. It is through selfless action, not through the expectation of a reward, that one truly discovers purpose and value. This commitment moves beyond simple acts of charity to embody a profound and enduring responsibility to contribute positively to the collective human experience.

Rigorous Self-Improvement is the internal work that complements external service. This involves a perpetual commitment to learning, developing one’s craft, and cultivating moral and ethical excellence. It requires the discipline to confront one’s own limitations, biases, and weaknesses, seeking always to refine the inner character. This demanding, continuous effort ensures that the individual is always growing in capacity and integrity, making their service more effective and their connections more authentic.

Finally, Deep Connection ties the inward and outward efforts together. This connection extends beyond superficial acquaintances to include profound empathy for others, a strong sense of belonging within a community, and a spiritual or philosophical bond with the cosmos itself. It is the recognition that personal well-being is inextricably linked to the well-being of all things. It is this depth of relationship that imbues both service and self-improvement with ultimate significance, confirming that the true rewards of life are found in mutual enrichment, not in the solitary pursuit of material gain.

Therefore, the genuine path is an arduous, comprehensive undertaking—a testament to human endeavor that fundamentally rejects the idea of a shortcut to success in favor of a life defined by ethical action, continuous growth, and profound interdependence.